Context

Context

Why do they want to build a data center in your territory?

The answer is a mix of economic, geopolitical, and technical reasons. Here, we explain what a data center is, why these infrastructures have become intentionally relevant in the digital economy, and why our governments are obsessed with installing them in their countries. Is it all as viable and inevitable as they make it out to be?

Part 1. The cloud is a data center: key definitions for its operation

Have you ever looked at the digital cloud where the magic happens, making our applications and information available in microseconds?

The digital cloud exists, but it is not as it is often imagined. The cloud is not in the sky but on the ground, in industrial neighborhoods, on indigenous lands, in deserts, and in cold areas. And the more digitized our lives become, the more abundant they are worldwide. The cloud is not immaterial; it is a concrete infrastructure that, if you look closely, can be seen in various places

“The cloud is not a cloud; the cloud is a data center.”

Here are examples of the cloud—data centers—in Sweden, the United States, and Chile.

Meta (Facebook) – Luleå, Sweden. Luleå Campus, northern Sweden ( source ).

Amazon data center in Boardman, Oregon, United States ( source ).

Google data center in the municipality of Quilicura, Santiago, Chile ( source ).

1. Definitions across three dimensions

Regardless of their location, they are usually gigantic buildings, quite similar to one another, and very nondescript. As can be seen, the physical architecture of data centers is not a particularly fascinating area of architectural advancement, and they tend to be deliberately unremarkable. Data center developers prefer to keep their facilities secure and out of public view. This means that it is not very common to know what these infrastructures are and what they are used for.

To explain it better, it is perhaps best to look at it in three dimensions: the role they play in making the internet possible, as infrastructures with their own functioning, and as a commercial typology, which today makes them a key sector of the digital economy.

a) Data centers in the internet infrastructure

In very simple terms, you can think of the internet as needing three levels of infrastructure to function.

The internet is an infrastructure made up of three main elements:

- Networks made up of fiber optic and copper cables, such as those used in telecommunications equipment like routers and switches, as well as in physical spaces like interconnection rooms and internet exchange points.

- Data centers are a crucial part of the internet infrastructure, as they store, process, and distribute digital data, and their continuous operation is vital for the functioning of the digital world.

- User terminals: smartphones, computers, tablets, connected objects, etc.

First, there are the networks, which are generally what we call telecommunications infrastructure, enabling the internet to function by allowing data to be transmitted via physical networks (such as fiber-optic cables) and wireless networks (such as Wi-Fi, 4G, 5G, and satellite).

However, for the internet to reach end users through their devices, such as smartphones and computers, data centers are essential. They are crucial because they facilitate a continuous and secure flow of data between networks and users, enabling online services, scaling resources, and providing global access to information through their strong connectivity, management, and physical and virtual security. These centers act as nerve hubs that house servers and equipment, efficiently connecting them to meet the evolving needs of users and organizations.

As seen, the more digitized our lives become, the more important these infrastructures become, to the point that today they are fundamental for processing, storing, and distributing large amounts of data, making them vital for Artificial Intelligence and the rest of the digital economy.

b. Data centers as self-operating facilities

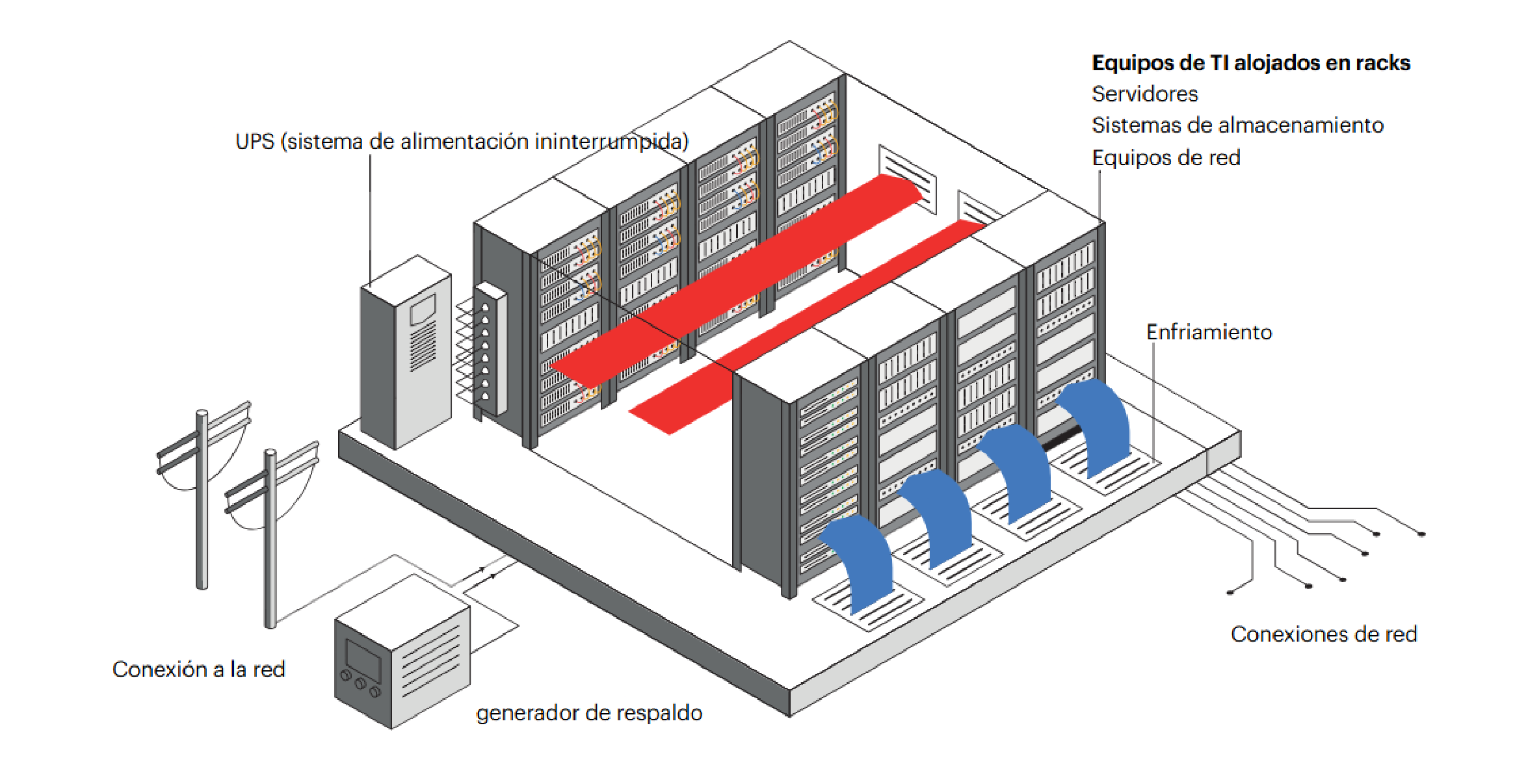

A classic definition of a data center is a specialized physical facility (ranging from a room to a purpose-built building) that houses and manages the IT infrastructure (including servers, storage devices, and network equipment) necessary to create, run, and deliver digital applications and services.

But to clarify how a data center operates, it’s helpful to look inside these facilities. The following illustrates the basic structure of a data center:

Inside these nondescript buildings, a few components are critical for data processing and storage and require intensive electricity use to operate 24 hours a day, seven days a week. These are racks that reach up to the ceiling, one after another, and house hardware infrastructure:

- Servers: computers that process and store data, equipped with central processing units (CPUs) and specialized accelerators such as graphics processing units (GPUs). They account for about 60% of the electricity demand in modern data centers.

- Storage systems: devices for centralized data storage and backup, which consume around 5% of the electricity.

- Network equipment: computers, routers, and load balancers that connect devices and optimize performance, accounting for up to 5% of electricity demand.

For the continuous operation of these components (in addition to powering lighting, office equipment, and other auxiliary systems), data centers need to have constant power; otherwise, they cannot function, and the digital cloud goes down. Thus, as part of the equipment that exists within these buildings, there are:

- Uninterruptible power supplies (UPSs) and backup generators ensure continuity of service during power outages. Although they are used infrequently, they are essential to the reliability of data centers. They are the primary sources of greenhouse gas emissions from these infrastructures because many emergency electric generators use high-powered diesel engines, which are preferred for their reliable power and rapid response to load changes. One data center that uses these types of generators is Google’s “Datacenter PARAM” in Quilicura (Santiago, Chile), which requires 645,878 kg of diesel fuel to operate (Evaluación Ambiental, 2017).

To measure how efficiently a data center converts total energy consumed into useful computing work, the PUE (Power Usage Effectiveness) metric is used. This ratio describes a facility’s overall energy costs. A PUE close to 1.0 means that almost all the electricity directly powers the computer equipment. The current industry average is approximately 1.5.

Operating continuously, the devices in the racks generate significant heat, necessitating the regulation of data center temperature and humidity to keep computer equipment in optimal condition. Incidentally, this level of heat can worsen significantly with the demands of AI. To cool them, various cooling processes are used that consume a lot of water. This is a critical point because it has been the focus of social and environmental controversies surrounding data centers.

c. Data centers as a commercial typology

Despite this architectural uniformity, data centers are specifically designed to meet the diverse customer demands worldwide, each with different priorities for latency, uptime, efficiency, and security.

Therefore, they respond to a variety of types that often overlap. For example: by the operator behind the data center company, the level of Internet connectivity of the operator, the size of the building, and even the level of information security (using a tiered classification system managed by the Uptime Institute, where Tier 1 has the least redundancy and Tier 4 is the most reliable).

From the perspective of operator types, until a few years ago, the prevailing model was for companies and governments to install their own data centers to meet their needs and purposes. These centers were usually managed internally by themselves through specialized teams. Typically, these facilities are located near the company’s headquarters or in a specific area that fulfills their latency requirements. In the case of governments, they are often situated in strategic locations to benefit from military security or to access private government fiber-optic routes.

However, that model has been changing in line with the changing digital technology market. Since the 2010s, both companies and governments have tended to move away from their own facilities and opt for colocation or cloud services to improve efficiency. This is, therefore, a different business model. Depending on the type of data center, lease agreements between the owner and the tenant vary considerably, although, again, these categories often overlap.

- Colocation data centers

Third-party facilities where companies or governments can rent space for their servers and other computer hardware. These third parties, who own the data centers, lease the physical space, power, cooling, and security, while also ensuring high-speed connectivity, all of which are essential for digital services to operate. However, it is the tenants who bring their own servers and network equipment or lease equipment from the colocation provider. Otherwise, long-term lease agreements are signed with the colocation provider. Colocation developers locate facilities close to their tenants’ needs and in locations where facility operations tend to be economically viable. The largest companies in this market are Equinix and Digital Realty (owner of Ascenty in Latin America). As shown below, colocation facilities function more like traditional real estate than cloud providers.

- Cloud

These cloud data centers offer computing resources and storage as a service over the Internet. Services can be quickly activated and deactivated, without needing long-term leases. The cloud is usually operated by cloud service providers such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud, which are often coincide with the so-called Big Tech companies. However, smaller providers can also offer cloud services. These providers serve as demand aggregators, bringing together many users to achieve economies of scale. Increasingly, companies are moving to the cloud because they see better returns by investing in their core businesses rather than in data center facilities. As a result, in recent years, these providers—especially Big Tech companies with available capital—are choosing to build extremely large (hyperscale) data centers. These are designed to support large amounts of data and computing workloads.

In general, cloud providers generate revenue through a metered approach. Users are billed based on their use of services, including storage capacity used, computing hours, use of cloud-provided software, etc. Cloud users can quickly and efficiently scale up or down their capacity, trading large upfront capital expenditures and long-term lease commitments for recurring cloud expenses.

There are three families of cloud services:

– IaaS (Infrastructure as a Service), which corresponds to the rental of computing and storage capacities.

– PaaS (Platform as a Service) provides customers with ready-to-use development platforms for developing and deploying their own applications.

– SaaS (Software as a Service) is a complete offering of business applications and software that customers pay for based on usage time or number of users.

Furthermore, a cloud can be:

– Public: shared among an unlimited number of customers.

– Private: it can be dedicated to a specific customer, tailored to their needs.

– Hybrid: combines the use of a public cloud (especially during periods of increased load) with a private cloud environment.

- Hyperscale

As we can see, hyperscale data centers overlap significantly with cloud data centers, especially when big tech companies own them. The most significant difference is size: cloud data centers can be any size, but hyperscale data centers, as their name suggests, are large facilities designed to house hundreds of thousands of servers and support rapid, massive growth in computing, storage, and networking capacity. For this reason, they typically exceed 50 MW of capacity and are deployed across multiple buildings on campuses.

They are generally owned and operated by large global technology companies such as Amazon (AWS), Microsoft (Azure), Google Cloud, Meta, or Apple. They do not sell data center space directly; they serve as the foundation for services such as Artificial Intelligence, the public cloud, social networks, and digital platforms.Their technical features include modular architecture, high levels of automation, and energy-efficient design (advanced cooling, renewable energy, proprietary hardware).

- Edge

These are small facilities strategically located closer to users or data sources. They are designed to reduce data delivery latency, providing faster response times and a better user experience, especially for real-time and latency-critical applications. As a result, companies can offer real-time services such as IoT applications, videostreaming, gaming, and virtual or augmented reality applications. Users include content delivery networks (CDNs), IoT service providers, and other applications that require low latency.

Edge data centers aim to monetize their proximity to end users. Their main business model is that companies pay for racks or space in small but strategic data centers (near cities, factories, 5G antennas). In other words, like the traditional colocation model, but in much smaller and more distributed facilities. But edge providers offer not only physical space, but also connectivity, security, and remote management. Here, customers can deploy low-latency applications without worrying about operating the hardware. Also, some operators allow customers to consume local computing and storage capacity on a pay-per-use model, similar to the cloud but closer to the user.

In addition, edge data centers serve as nodes for telecommunications operators, offering computing capacity at 5G base stations. Instead of sending all data to a distant data center or the central cloud, processing is done at the edge of the network, right at the base station or in a small nearby data center. This allows data to be processed with very low latency (milliseconds). For example, an autonomous vehicle connected to 5G needs to process camera images to brake in time: if it sent that data to a data center in the US, it would take too long; instead, processing is done in a local edge data center connected to the 5G antenna.

Data centers: infrastructure without architecture

Fanny Lopez & Cécile Diguet (2019) believe that the absence of architecture dedicated to digital infrastructures, and more specifically to data centers, could be explained by the following reasons.

- A historical reason: data centers are an almost organic extension of server cabinets and IT rooms originally built into office buildings, research centers, and universities. Today, only the scale has changed: the cabinet is much larger. Otherwise, the internet’s initially decentralized nature favored a multiplicity of actors and uncoordinated development, without an overall vision, which could have led to a deeper architectural reflection.

- The rapid development of the internet: when the commercial web was created in the early 1990s, data centers rushed to locate themselves near internet exchange points, strategic crossroads of the web and the internet. Everything quickly became focused on gaining market share. Many data centers were set up in historic telecommunications buildings, buildings already used by the electronics industry, and former industrial sites.

- The major players in the colocation sector (such as Digital Realty, CoreSite, and Equinix) are primarily real estate investment funds. The 2000s, and especially the 2010s, saw a period of construction of new data centers in dedicated buildings, but investors’ priority was a quick return on investment for the facility. In other words, the creation of specialized architecture or the installation of a heating network is considered an additional cost, justifiable only if the administration where the infrastructure is located has made an urgent request. Colocation data centers (which therefore exclude those of companies or clouds such as Google or Microsoft) have become high-yield real estate products, so there is rarely any architecture.

- The design contributes to the creation of an invisible digital technical system, which we now know as “the cloud”: In other words, the envelope of the infrastructure does not suggest the strategic importance of its content, which contributes to its discretion and the creation of the cloud.

However, on a larger scale, some data centers strive to integrate the facilities into the surrounding architecture and landscape.

Part 2. The data center boom in the 21st-century economy

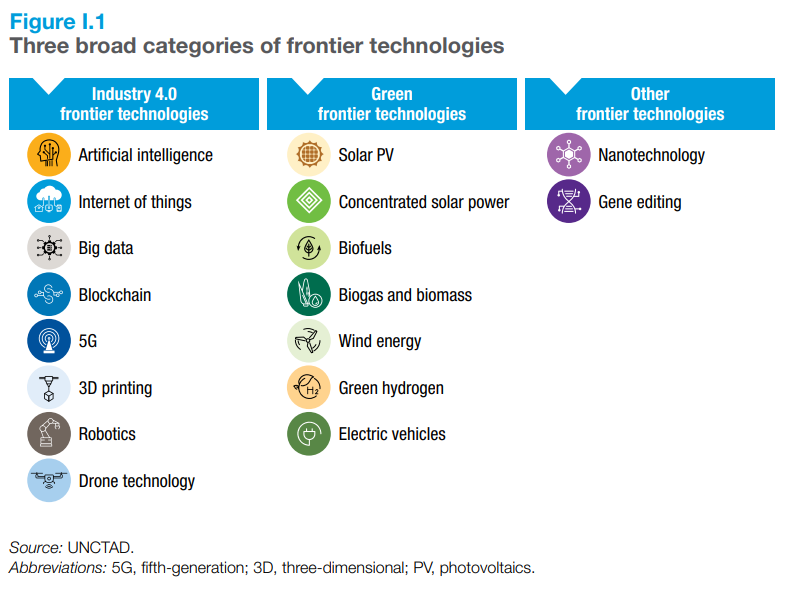

Digitalization has changed the economy forever to the point where it is difficult to talk about a digital economy as opposed to one that is not. Global phenomena such as the COVID-19 pandemic precipitated the digitalization of economies so they could continue to function in part. But particularly in recent years, the rapid emergence of so-called “cutting-edge technologies,” in particular artificial intelligence (AI), is profoundly transforming our economies and societies, reshaping production processes, labor markets, and the ways we live and interact (UNCTAD, 2025).

1. AI and its growing market value

AI is the discipline of computer science that seeks to develop systems capable of performing tasks that usually require human intelligence, such as learning, perception, reasoning, decision-making, and language comprehension.

- It is based on algorithms, mathematical models, as well as machine learning and deep learning techniques.

- Its applications include virtual assistants, voice and image recognition, autonomous vehicles, predictive analytics, machine translation, and advanced chatbots, among others.

In 2023, cutting-edge technologies represented a market worth $2.5 trillion, and this is projected to grow sixfold to $16.4 trillion over the next decade. By 2033, AI is likely to be the leading technology, with a market size of around $4.8 trillion. Ongoing advancements are making AI more powerful and efficient, boosting its adoption across many sectors and activities, such as content creation, product development, automated coding, and personalized customer service.

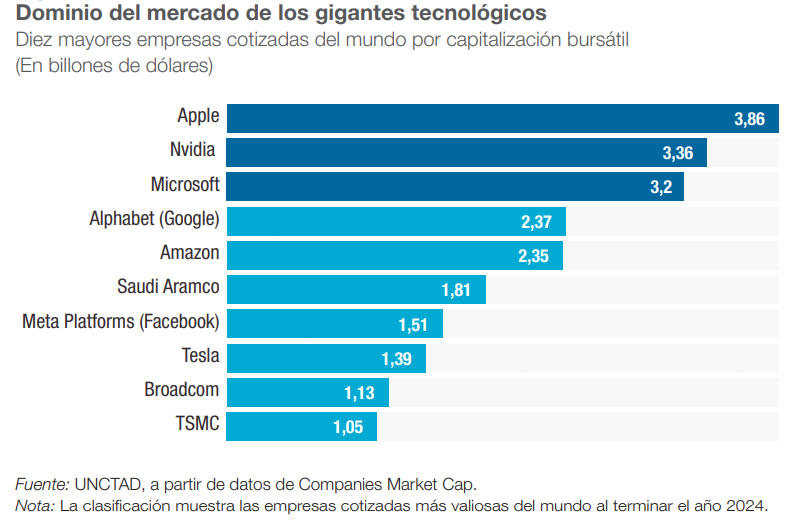

The leading providers of advanced technologies are currently among the world’s largest companies by market capitalization. The market values of Apple, Nvidia, and Microsoft each surpass $3 trillion, which is close to the gross domestic product (GDP) of the African continent or that of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the world’s sixth-largest economy.he five most prominent companies are from the United States, and three of the top chip manufacturers—Nvidia, Broadcom, and TSMC2—are among the ten most significant globally; nearly all focus on advanced technologies and are investing heavily in AI.

There is also a significant concentration of investment in research and development (R&D). In 2022, 40% of corporate-funded R&D worldwide was concentrated in just 100 companies, about half of which were based in the United States, led by Alphabet, Meta, Microsoft, and Apple. Market dominance, both at the corporate and national levels, could widen global technology gaps, making it even more difficult for laggards to catch up.

2. AI as a geopolitical struggle

Today, we are witnessing a geopolitical race against time between the United States and China (with the European Union lagging far behind and not really in the running) to achieve economic supremacy in this arena, cleverly dubbed “the Artificial Intelligence race.” Rising trade barriers characterize strategic competition in AI, heightened competitive ambitions, and the struggle to secure control over the data and digital tools of the future.

The strategic rivalry between the United States and China over AI has deepened, leading to talk of a new “digital Cold War.” Both superpowers consider leadership in AI to be a defining element of national power and are mobilizing state resources to secure it.

In this context, over the past three years, the United States has pursued a comprehensive strategy to strengthen its global leadership in artificial intelligence. For example, the CHIPS and Science Act (2022) allocated more than $52 billion to semiconductor manufacturing and R&D, securing the key input for training frontier models. In 2023, the US imposed export controls on AI chips to China, expanded to cover models such as Nvidia’s A800 and H800, to limit strategic competitors’ access to advanced technology (CNN, 2023). In 2025 (AP), the Trump administration revoked EO 14110. It replaced it with Executive Order “Removing Barriers to American Leadership in AI,” which revokes the previous policy to prioritize deregulation and rapid growth, while maintaining technological controls as the primary security tool—an approach reinforced by a controversial agreement allowing the export of AI chips to China, with a 15% commission for the U.S. government (AP, 2025).

Despite US efforts to maintain its technological superiority by restricting China’s access to advanced AI chips, the Asian country has made surprising progress. Export controls should have maintained a 2–3 year advantage for the US, but this no longer seems sufficient, as companies such as Alibaba and Tencent have made significant progress (Time, 2025). Meanwhile, China is betting heavily on bringing artificial intelligence from the laboratory to the real world, positioning it as a key tool in sectors such as health, public safety, education, and even the fight against corruption. Meanwhile, the US approach remains focused on developing state-of-the-art AI models, whereas China prioritizes practical applications, broad governance, and open collaboration. Although there is enthusiasm for the pace of progress, doubts remain about whether the infrastructure and capital available in China will be sufficient to sustain the strategic momentum (The Washington Post, 2025).

The result is an increasingly fragmented global technology ecosystem. U.S. allies in Europe and Asia are under pressure to take sides or split their supply chains. Many have aligned themselves to some extent with U.S. restrictions on exports to China, but few are comfortable with a complete break, given China’s role as a market and supplier (WEF, 2025).

Similarly, amid this geopolitical struggle, as confirmed by the UNCTAD report on AI (2025), there is a significant gap in AI between developed and developing countries. In terms of infrastructure, for example, the United States has about one-third of the 500 largest supercomputers and more than half of global computing power.

Most data centers are also located in the United States. Apart from Brazil, China, the Russian Federation, and India, developing countries have limited AI infrastructure, which hinders their ability to adopt and develop this technology. The AI gap is also evident across service providers, investment, and knowledge creation.

Trying not to get stuck in this obvious gap in AI-dominated digital economies, the rest of the countries, meanwhile, are also rushing to establish a presence in the global AI production chain. This is the case in Latin America, where governments are rushing to attract investment from the big players in AI. But our continent’s presence in the global production chain in the 21st-century economy is very similar to that of the 20th century: offering natural resources at low prices.

Whether it is the metals and minerals found in microchips and other computer components, or labor, land, water, and cheap renewable energy to power data centers, our presence in the global chain does not offer much added value and, in return, receives few jobs, faces serious socio-environmental consequences, and, incidentally, ends up paying a high price for the very technology that, in many material respects at least, we support. As UNCTAD said in its report on the digital economy and sustainability (2024): “There is a fundamental need to reverse trade imbalances, wherein developing countries export raw minerals and import higher value added manufactures, which contributes to an ecologically unequal exchange.”

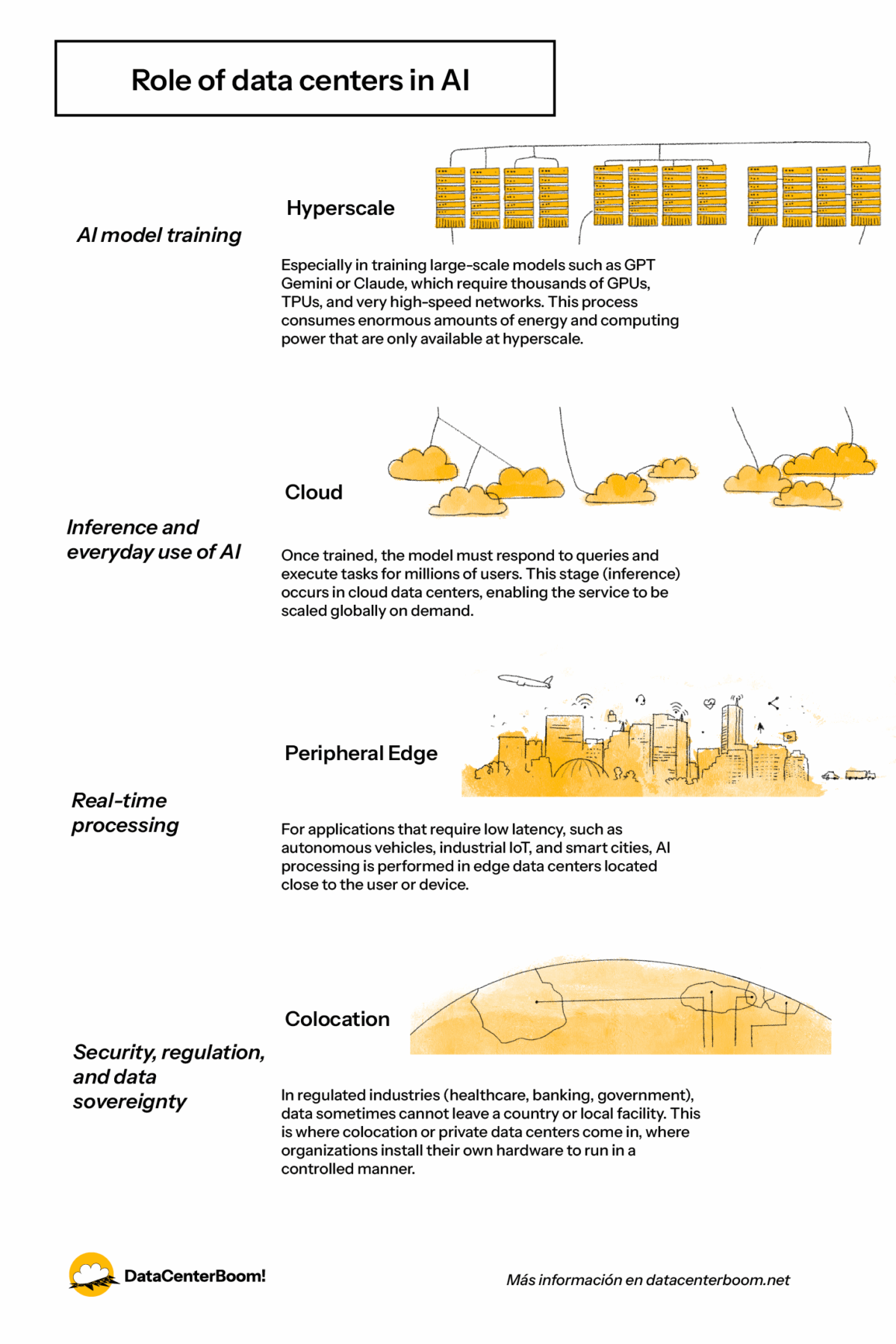

3. The role of data centers in AI

This is the geopolitical context that explains why Latin American countries are increasingly competing to attract AI data centers: these infrastructures are considered a prime asset in the digital economy (Valdivia, 2024). These extensive server farms manage more than 95% of global internet traffic, supporting everything from video streaming to cloud-based artificial intelligence services. Whether for training or using its algorithms, AI requires not only a connectivity infrastructure (telecommunications) but also a robust digital computing infrastructure, understood as the set of technologies and systems that enable the creation, processing, storage, and transmission of data. For the WEF (2025), data centers, once considered back-end infrastructure, have become strategic assets: the digital equivalent of power plants or ports.

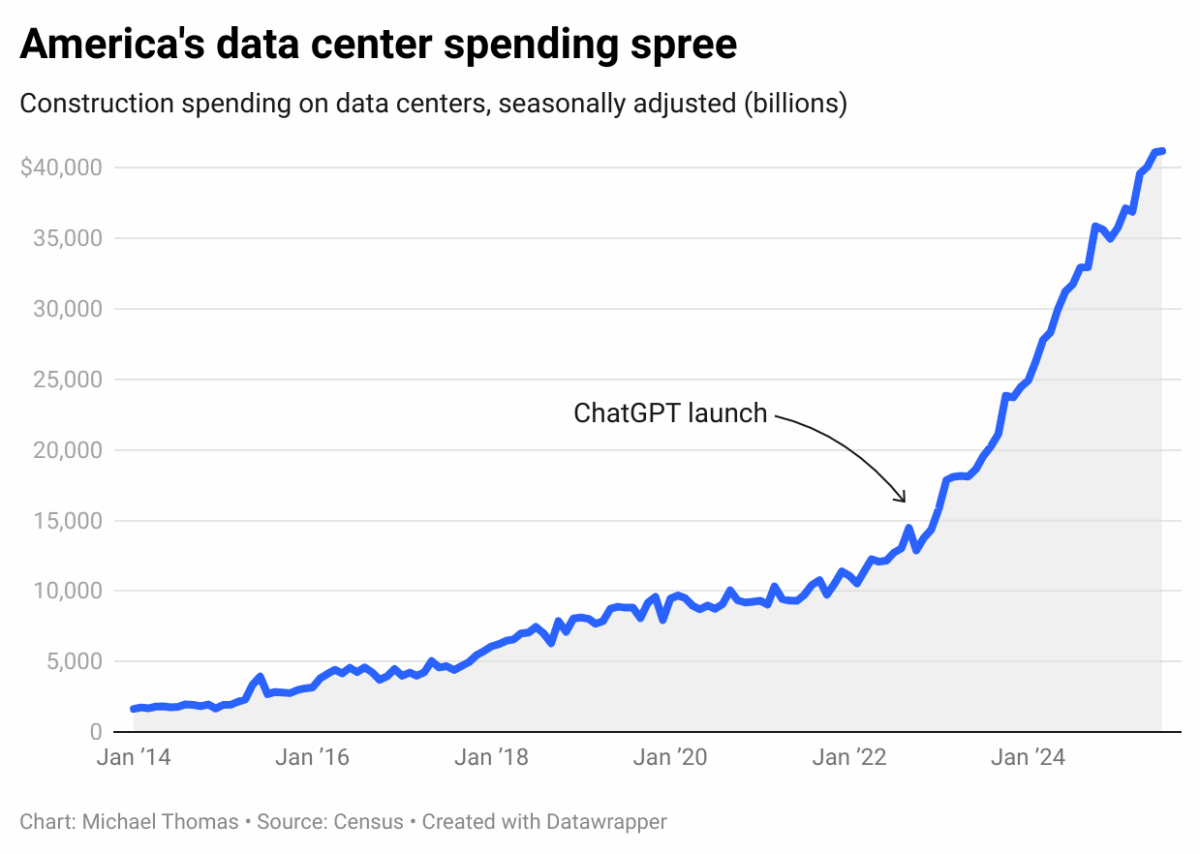

However, since the launch of ChatGPT in November 2022, technology companies have invested heavily in building data centers. As Michael Thomas (2025) reports, in just three years, spending on data centers in the United States has risen from $13.8 billion to $41.2 billion per year, an increase of 200%. This has occurred at a time when virtually all other construction activity in the country has slowed.

The US alone hosts approximately 51% of the world’s data centers, a concentration that underscores both the country’s digital dominance and other countries’ reliance on US cloud services. This dominance has prompted many different nations and regions to accelerate the development of their own data center capacity, aiming to ensure that their data resides on their own territory.

Data centers have therefore become a focus of industrial policy. Around the world, countries offer tax incentives and expedited permits to attract new server farms. Emerging economies view data centers as the foundation for future growth, attracting large technology companies to establish regional hubs.

The goal is not only economic, but also digital resilience. Hosting a large data center can attract related industries, such as cloud services and AI research, while reducing dependence on foreign connectivity. In a crisis, controlling national data storage could be as important as controlling the power supply.

However, this new importance brings with it a new vulnerability. Geopolitical tensions are casting a shadow over the data center industry, as supply chains and critical components —from advanced chips to fiber-optic cables—are now embroiled in trade disputes.

Export controls and sanctions can restrict access to the latest processors required for modern data centers. For instance, export bans on high-performance AI chips made by US companies have compelled Chinese operators to look for alternatives.

These restrictions emphasize that a data center’s level of advancement depends on the components it can import, elevating these facilities from behind-the-scenes technology to key players in global security concerns.

4. Boom! Is this a bubble?

Grand View Research’s “Data Center Market Size And Share | Industry Report, 2030” (2025) states that the global data center market was valued at approximately $347.60 billion in 2024. By 2030, it is expected to reach USD 652.01 billion, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.2% between 2025 and 2030. This growth is mainly due to the expansion of digital transformation, the adoption of cloud computing, and the implementation of emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), machine learning (ML), and the Internet of Things (IoT). North America had the largest market share in 2024, with more than 40% of the total. Asia-Pacific was the fastest-growing region.

But the rapid growth of data centers, especially in the United States, is linked to the boom in global artificial intelligence economies. Both AI and its derivative infrastructures, especially data centers, have been questioned: will they be the next economic bubble that, amid so much financial speculation, cause economies to burst?

Many authors, including The New Yorker’s economics and business columnist John Cassidy (2025), suggest there are enough signs to compare the current excitement about artificial intelligence with the dot-com bubble of the 1990s. They point out similarities such as excessive speculative investments, spectacular IPOs, and high valuations without clear backing in real profits. However, unlike during the dot-com boom, large companies like Nvidia, Microsoft, and Apple are showing solid profits. Still, there are concerning signs: Palantir reached a valuation close to 600 times its profits and 130 times its sales, figures that would have raised suspicions even during the dot-com bubble. Additionally, Figma’s initial public offering soared 250% in a single day, reminiscent of similar gains in the 1990s.

Doubts about the bubble extend to the rush to build data centers for AI. Various sources agree that the current massive expansion in the United States reflects both enthusiasm for AI and potential risks of a financial and infrastructure bubble. For example,For example, many of these projects are financed without clarity about future profitability (Futurism, 2025). Joe Tsai, president of Alibaba, stated that signs of a bubble are already apparent: many data centers are being built without contracts to secure customers. He particularly criticized the massive investments in the US, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars, based more on expectations than on proven demand (Quartz, 2025). Indeed, the United States is experiencing a “gold rush” in data center construction. However, the lack of coordination between the federal government and the states threatens to lead to duplicate investments, tensions in local communities, and unsustainable public costs (Atlantic Council, 2025). In contrast, other sources say that demand for AI computing capacity remains strong, but we are seeing a strategic pause in some projects by big tech companies, aimed more at reorganizing investments than at a definitive halt (CNBC, 2025).

Amid the AI boom, China launched hundreds of data center projects between 2023 and 2024: more than 500 were announced, and at least 150 were operational by the end of 2024. Many of these are now underutilized due to poor planning, changes in demand (e.g., the shift from training to inference workloads), and technical issues. The facilities have become costly burdens with low utilization rates (MIT Technology Review, 2025). Furthermore, local sources reported that up to 80% of the capacity of newly built AI data centers in China remains idle (TechRadar, 2025).

However, data centers are among the fastest-growing asset classes in commercial real estate, especially in emerging markets. Much of this growth is focused on so-called “secondary markets,” such as Latin America. In fact, according to Research And Markets’ “Latin America Data Center Market Landscape (2025–2030)” report (2025), the Latin American data center market was valued at $7.16 billion in 2024. It is expected to reach $14.3 billion by 2030, with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 12.22%.

As we will see throughout DataCenterBoom!, data centers consume significant resources and require substantial energy, water, and land. More external space near urban centers is needed, as well as a reliable supply of water and energy, more than ever before to support the large amount of computing and processing capabilities for AI and 5G technology. This unprecedented rapid growth has required careful infrastructure planning and financing by governments and private investors. A bursting of the bubble, even in the United States, would have consequences in Latin America.

For Alfonso Marín Muñoz (2025), an energy expert, it is not unreasonable to talk about a bubble. “There is already speculation about land, long-term energy contracts, and technologies that are not yet mature, as if they were pure gold. All this is based on the premise that digital demand will continue to grow indefinitely. But what if this is not the case? What if it stabilizes? What will happen when the price of electricity rises or the rules of the game change due to regulatory or environmental factors?”

Part 3. Where is the business? Factors in deciding where to install a data center

For data center operators, the highest priority is to maintain constant data access for their customers, which requires uninterrupted uptime. This makes the smooth operation of facilities and auxiliary systems, including cooling, IT support, and security, absolutely essential. Downtime, as opposed to uptime, happens when these operations are interrupted, resulting in various economic costs and practical impacts depending on the services they support.

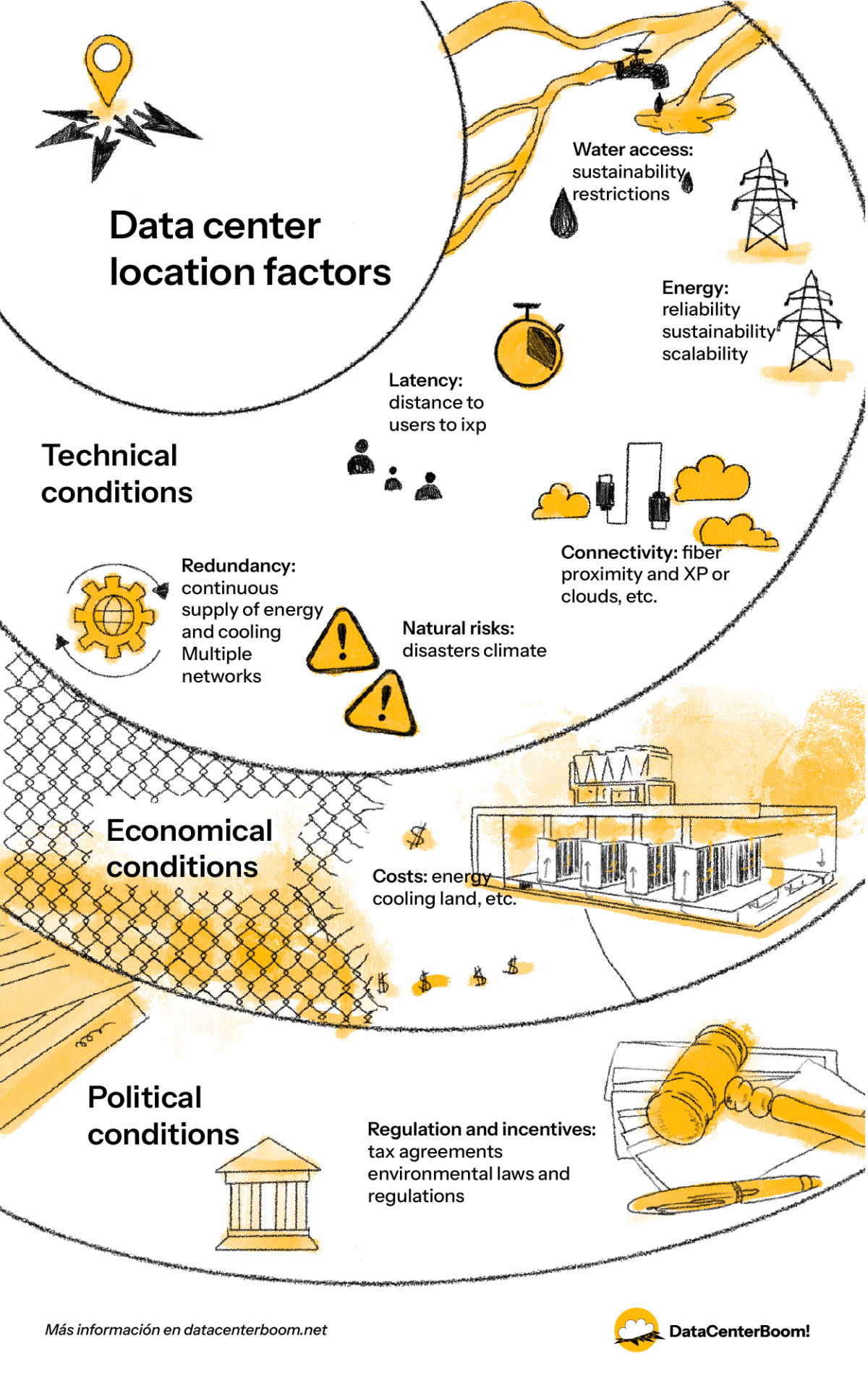

Providing uninterrupted service involves several technical, economic, and political conditions that are considered when selecting a site for a data center (Fawcett, 2024):

a. Latency

Latency is the time it takes for data to travel between a user’s device and a data center, typically measured in milliseconds, and directly affects the response speed of applications, websites, and cloud services. Latency is important for artificial intelligence (AI), as many AI applications require real-time or near-real-time processing. For example, autonomous vehicles, industrial robots, fraud detection systems, and virtual assistants rely on AI models that must analyze data and respond instantly; high latency can cause delays that reduce accuracy, efficiency, or even safety. When training large AI models, low latency between servers and storage also speeds up data transfers, making the process more efficient. Similarly, in inference (when AI models are used to make predictions), reducing latency ensures a smoother user experience across applications such as chatbots, medical imaging, and augmented reality. It all depends on the services: some use cases require the lowest possible latency, while other applications can tolerate longer wait times.

Thus, when choosing a data center location, it is essential to consider the latency required for the tasks to be implemented. Data centers are often built near large population centers, major Internet exchange points, or regions with strong connectivity infrastructure. Traditionally, data centers have prioritized proximity to large metropolitan areas, near the company’s headquarters, or where data is expected to be accessed. Some use cases dictate that the data center should be located near users; other cases suggest that data should be located near other data.

b. Redundancy

While latency focuses on reducing delays in data transmission, redundancy ensures continuous operation and resilience against failure. Redundancy focuses on reliability, specifically having backup systems for power, cooling, and network connectivity so that services continue to function even if one component fails.

A well-located data center that meets redundancy standards should be able to connect to multiple power grids, have uninterruptible power supply (UPS) systems and backup generators, and employ redundant cooling designs such as N+1 or 2N, as well as multiple fiber routes. This ensures that even if one system fails, services remain online, which is vital for mission-critical workloads.

c. Connectivity

Connectivity highlights the importance of access to robust digital infrastructure. Locations with dense fiber networks, multiple carrier options, and proximity to major IXPs are best suited to deliver low-latency services and avoid bottlenecks. Integration with edge infrastructure and 5G networks is also becoming an increasingly important consideration.

d. Energy

Data centers operate thousands of servers 24 hours a day, consuming large amounts of electricity, not only to power the computer equipment, but also to run the cooling systems that prevent overheating. This means that access to a stable and affordable power supply is essential for both day-to-day operations and long-term financial viability. Without it, the facility risks incurring higher costs, downtime, or even being unable to serve customers.

Beyond affordability, energy reliability is another crucial consideration. Data centers cannot afford interruptions, as downtime could disrupt essential services such as cloud computing, banking, e-commerce, or healthcare. For this reason, locations with robust energy infrastructure, such as multiple independent grids, redundant power lines, or large backup generation capacity, are preferred. Areas prone to blackouts or unstable power supplies can pose significant risks, requiring costly investments in backup systems.

At the same time, sustainability and environmental responsibility have become key considerations in energy. With growing global pressure to reduce carbon emissions, companies are increasingly choosing locations with abundant renewable energy sources, such as hydroelectric, wind, and solar power. Large-scale operators such as Google, Amazon, and Microsoft often commit to powering their data centers with 100% renewable energy, which influences location selection. Therefore, regions that offer clean, affordable, and scalable energy options are much more attractive than those that rely on fossil fuels.

Finally, regulatory and reputational factors related to energy use are also critical. Governments are increasingly enforcing environmental regulations and carbon-reduction targets, which can affect both the availability and the cost of electricity. In addition, customers and stakeholders expect companies to prioritize green energy, making sustainability not only an operational choice but also a strategic and reputational one.

Access to energy as a factor in developing countries

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and its “Energy and AI” (2025) report, while emerging and developing economies (excluding China) account for 50% of the world’s internet users, less than 10% of global data center capacity comes from there. In regions with frequent power outages or poor power quality, maintaining a data center can be risky or costly, making overseas hosting more attractive to businesses. This could be an opportunity for developing countries with a track record of reliable, affordable energy, as they will be better positioned to secure the computing power essential to growing data centers.

e. Water availability

As with electricity, the stability of the water supply is essential. Data centers generate enormous amounts of heat, and many facilities rely on water-based cooling systems (evaporative cooling, chilled water systems) because they are often more energy efficient than air-based systems alone. A secure, continuous water source ensures uninterrupted cooling and prevents overheating, which could lead to downtime or equipment damage. This means that proximity to reliable water sources is an important consideration when choosing a location.

In regions with water scarcity, the use of large volumes of fresh water for cooling can create tensions with local communities and industries. Companies such as Microsoft and Google have been criticized for the water consumption of their data centers, especially in drought-prone areas. This has made water consumption a reputational and environmental issue, not just an operational one.

f. Natural risks

Natural risks refer to external conditions that can threaten the operation of a data center. Natural disasters, such as earthquakes, floods, or hurricanes, can cause service interruptions or damage infrastructure. Political stability and security risks are also considered, along with the local climate, which influences cooling costs.

g. Regulation and incentives

Finally, regulation and incentives reflect the role of policy in location decisions. Data sovereignty laws may require data to be stored within certain jurisdictions, environmental regulations may influence design and operations, and tax breaks or investment incentives may tip the financial balance in favor of one location over another.

Regulatory and zoning restrictions related to land use can impede or facilitate projects. Some regions offer industrial zones explicitly designed for data centers, with tax benefits and pre-approved permits, while others may impose environmental or noise regulations that slow development.

h. Costs

The costs of a data center fall into two broad categories: CapEx (capital expenditures) and OpEx (operating expenditures). CapEx is the initial investment required to build the data center, while OpEx is the recurring expenses to keep it running continuously and safely.

The relationship between CapEx and OpEx is strategic: a higher initial investment in efficient cooling technologies or renewable energy can significantly reduce long-term operating costs. In contrast, a more austere design with reduced CapEx can lead to much higher OpEx due to higher energy consumption and frequent maintenance requirements.

- Capital expenditures (CapEx)

On average, building a data center costs between $7 million and $12 million per megawatt (MW) of installed IT capacity, depending on the Tier level, location, and business model (hyperscale, colocation, or enterprise).

The most relevant items in these expenses are:

– Land purchase

Land availability and cost are crucial factors that affect expenses. Data centers need large parcels of land to accommodate server rooms, cooling systems, electrical gear, and often space for future growth. Land close to power grids, renewable energy sources, and water supplies reduces infrastructure costs and improves sustainability. Similarly, proximity to fiber-optic routes or Internet exchange points ensures strong connectivity. In urban areas or regions with limited space, high real estate costs can make projects less feasible. Conversely, rural or semi-rural locations often have cheaper land, but this must be balanced with other factors such as connectivity and latency.

Both hyperscalers and real estate data center developers engage in an activity called “land banking.” They accumulate land in attractive locations five, seven, or ten years before they even begin construction. Many developers have hundreds, if not thousands, of acres of land in their portfolios. They gradually add capacity, so they could launch a project of, say, 50 or 100 megawatts every two years. This depends largely on the capital available and when they expect the lease to begin.

– Electrical infrastructure

Currently, the most difficult challenge in the industry is finding or supplying power to a developing site. A relevant industry metric is the cost of new energy (CONE), the cost of providing power to a site. There are three primary levels of electrical infrastructure: generation, transmission, and distribution. Limitations can arise at any of these three levels, requiring improvements to supply the site with the necessary electricity.

Electricity is generated at the power plant. To efficiently transmit it over long distances, the voltage or the speed of the electricity is increased to reduce energy loss due to resistance. Substations are used to raise or lower these voltages. Distribution lines, such as the power poles commonly seen in cities, are the final part of the electrical system that delivers electricity to consumers.

When a data center developer requires more electrical capacity than the local utility can provide, the developer is usually responsible for funding the necessary infrastructure upgrades. Furthermore, even if the developer finds it economically viable to proceed with such an investment, there is no guarantee that the local utility can deliver within a reasonable timeframe. Supply chain issues impact the electric power industry.

Data center developers typically maintain standardized equipment across their portfolio, can pre-order equipment years in advance, and can reasonably predict how much capacity they can deploy. This pre-order strategy does not extend to external infrastructure equipment, as each utility may have different product designs and specifications.

Power systems (UPS, generators, substations, and distribution) usually make up about 40 to 45% of the total cost.

Power for leases

Unlike traditional real estate leases, data center leases are based on power in watts rather than square footage, highlighting the power-centric nature of data center operations and the critical importance of power supply to their users. Megawatts (MW) and kilowatts (KW) are the current basic units of measurement in the industry. As the industry grows, gigawatts (GW) are increasingly being used, especially to measure supply and absorption in a given market or at the national level.

– Cooling systems

Cooling a data center is a significant undertaking, and the mechanical equipment required far exceeds the traditional air conditioning systems used in commercial buildings. Therefore, building a data center involves significant investments in cooling systems, which account for a substantial portion of both construction costs (CapEx) and operating costs (OpEx). In medium-sized projects (approximately 800 kW), cooling is estimated to account for 15% to 20% of total CapEx. In contrast, “power and cooling” together can account for up to 60% of the budget, with power itself consuming 40% to 45% of CapEx.

– Design and construction

Due to its austere design, the predominant construction method is precast concrete, similar to that used for industrial buildings. This involves building extensive formwork, filling it with concrete, and then using cranes to place the walls in position. The roof is composed of steel beams, metal sheeting, and a roofing membrane. The clear advantage of this approach is the significant cost savings and speed with which they can be built, making them an efficient option for large-scale data center construction.

The facilities look very similar to each other. Data center developers create a standardized design that meets their computing and cooling objectives, then replicate it multiple times across the site.

Instead of adapting the design to the terrain and creating a single large building, they chose a site large enough to hold multiple buildings in their plan and constructed them sequentially. For example, the standard AWS facility is designed to supply between 25 and 32 MW; to increase the power available at a specific site, the same building is built multiple times.

This standardization has many clear advantages. The first is that the design of their facilities has been optimized over many iterations to balance electrical, computing, and cooling loads. Only minor adjustments are needed to comply with local regulations or climatic conditions. Construction teams are familiar with the design, minimizing interpretations or questions in the field. In addition, construction materials and technical equipment can be planned and ordered years in advance. Annual operating expenses can be projected across the portfolio, with slight adjustments to account for specific nuances in each geographic area.

Building a data center requires specialized construction firms certified to specific technical standards, as these facilities are far more complex than typical commercial or industrial buildings. A data center must house highly sensitive computer equipment and operate continuously with minimal downtime, requiring precise integration of advanced electrical, mechanical, and structural systems. Unlike standard office or warehouse projects, data centers must accommodate high-capacity fiber connectivity, complex cabling, UPS (uninterruptible power supply) systems, and advanced cooling systems. All these components need to function perfectly to prevent overheating, power outages, or security breaches. To meet these standards, builders with proven experience in mission-critical infrastructure are usually necessary.

– Acquisition of IT equipment

This equipment includes servers, storage systems, switches, routers, and firewalls, along with the software and associated licenses required for their operation. The magnitude of this investment depends on the necessary level of redundancy, the planned rack density, and the types of applications to be hosted (for example, artificial intelligence workloads require high-cost GPUs, which substantially increase costs).

In addition, in hyperscale or colocation data centers, customer diversity may require more flexible architectures that increase initial costs, as they must support diverse virtualization, security, and connectivity environments.

Finally, it should be noted that the weight of IT equipment spending within CapEx varies depending on the data center’s business model (Weinschenk, 2024; TAdviser, 2025). In a corporate-owned data center, the percentage can exceed 20% of total CapEx, since the infrastructure is tailored to the company’s needs. In contrast, in colocation or hyperscale data centers, the operator tends to focus more on electrical infrastructure, cooling, and security, allowing customers to install some of the hardware, which reduces the IT CapEx component of the initial investment.

Unlike other CapEx components, IT equipment depreciates the fastest. While an electrical or cooling system can remain operational for 10–15 years with proper maintenance, servers and network devices usually have a useful life of about 3-5 years, requiring more frequent replacement. Therefore, initial CapEx is often paired with a financing strategy or hybrid models that include hardware leasing to lessen the impact of replacement.

Depreciation

In addition to computer hardware, mechanical and electrical systems also depreciate and require regular repairs and maintenance, making them a continuous operating expense. Power distribution units (PDUs) and uninterruptible power supplies (UPSs) are critical components that support the redundancy measures in a data center. To ensure uptime guarantees, this equipment must be inspected and replaced periodically. The average lifespan of data center land is typically between 25 and 30 years. Cooling equipment has a lifespan of between 10 and 15 years. Some electrical components, such as transformers, uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), and power distribution units, have a lifespan of 8 to 20 years.

- Operating expenses (OpEx)

OpEx covers all the expenses needed to run the data center day to day. Most of it is for electricity, which can be 30% to 50% of operating costs, since it’s needed to power the servers and keep them cool. It also includes costs for specialized staff, physical security, equipment maintenance, redundant telecommunications links, insurance, and taxes. According to industry estimates, annual OpEx is approximately 5-10% of the initial CapEx, meaning a data center with a $100 million CapEx can spend between $5 million and $10 million per year on operations.

– Electricity consumption

Energy is a continuous, significant operating expense. However, that does not mean that all data centers will be concentrated in areas with the lowest electricity rates. According to Fawcett (2024), a comparison between states with the lowest electricity rates (based on data from the Energy Information Administration, EIA) and the number of data centers in operation (per MW) reveals that there is no linear relationship between the two. States such as Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Arkansas, despite their cheap electricity, have few data center facilities. Factors other than low electricity costs influence decisions about data center location.

– Personnel and training

Another significant operating cost associated with data center facilities is personnel. Network engineers are responsible for maintaining the uptime guaranteed by these facilities. Their duties include installing and configuring new hardware and performing routine maintenance.

Although there is no exact data on the number of employees needed to operate a data center, industry experts estimate that approximately one full-time employee or contractor is required for every MW of large-scale contracted power. It is important to note that this figure is highly subjective and will depend mainly on the uptime tier structure and standards adopted by each operator.

This role requires ongoing training and hiring of new staff to ensure personnel are skilled in working with all technologies. A practical concern in developing new facilities is ensuring there are enough personnel in the area to staff them. Many locations that seem attractive become hard to manage long-term because attracting and keeping talent in remote areas is difficult.

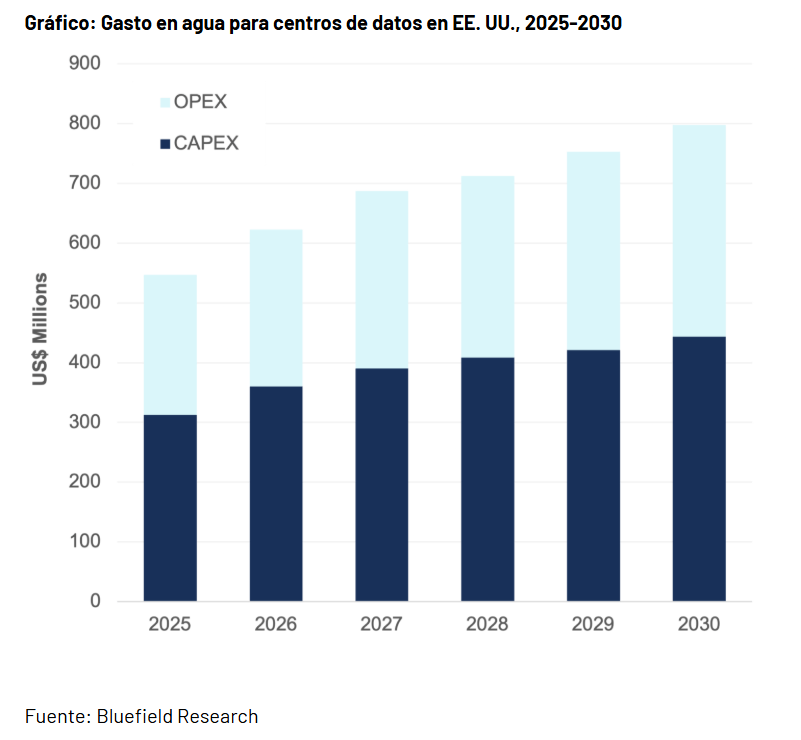

Water as OpEx

There are no clear or standardized figures on the exact percentage of water consumption within a data center’s OpEx (operating expenses): the available information focuses more on absolute volumes (total liters or dollars) than on percentages of total operating expenses. The reason may be that consumption is highly variable: it depends on cooling type, climatic location, reuse systems, etc., and there does not seem to be a single representative value. However, a report by Bluefield Research (2025) projects that by 2030, water-related expenses (both CapEx and OpEx) in US data centers will reach $797 million annually, although it does not specify what proportion this represents of total OpEx.