Impacts

Impacts

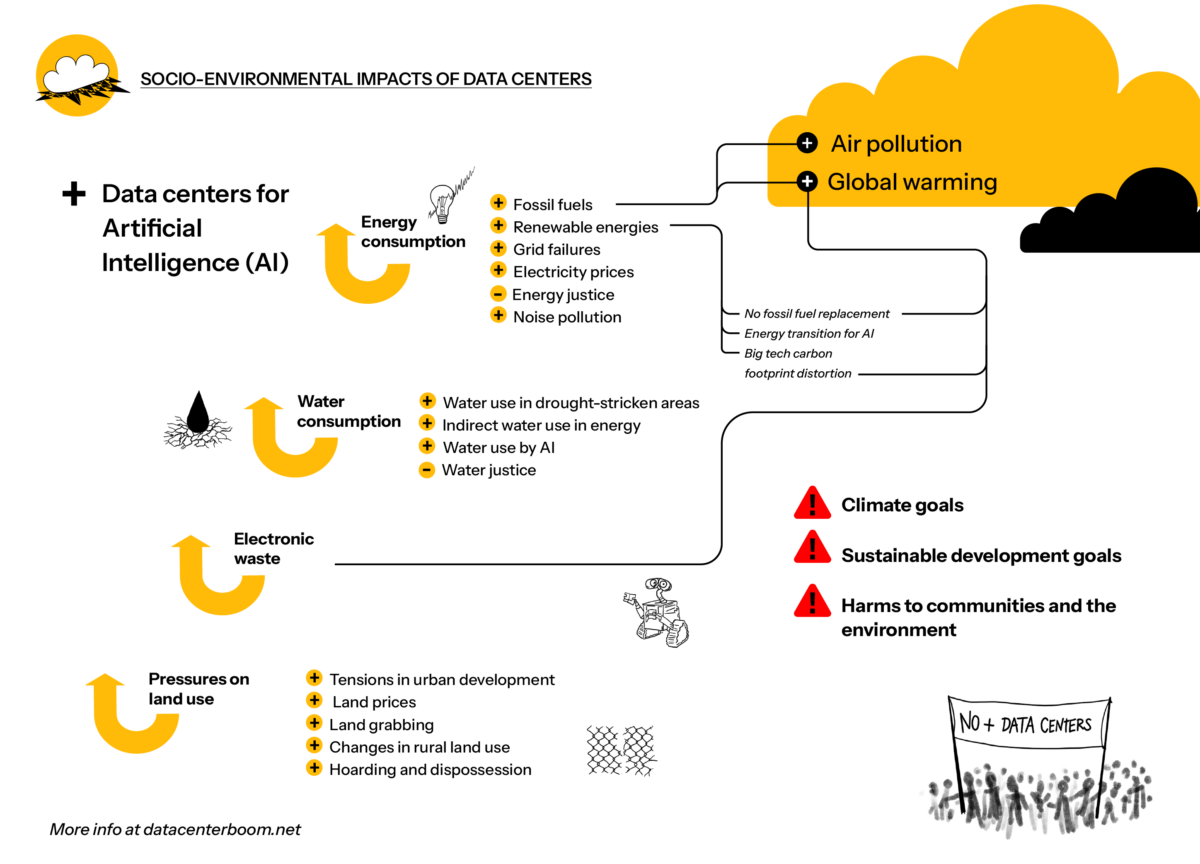

The socio-environmental conflicts of data centers

As data centers multiply, controversy over their profound socio-environmental consequences is growing worldwide. In Latin America, their impacts have different nuances that resonate with historical challenges. Here is a catalog of effects behind "the cloud" to help you understand the socio-environmental conflicts in your community.

Part 1. Increased energy consumption and its consequences

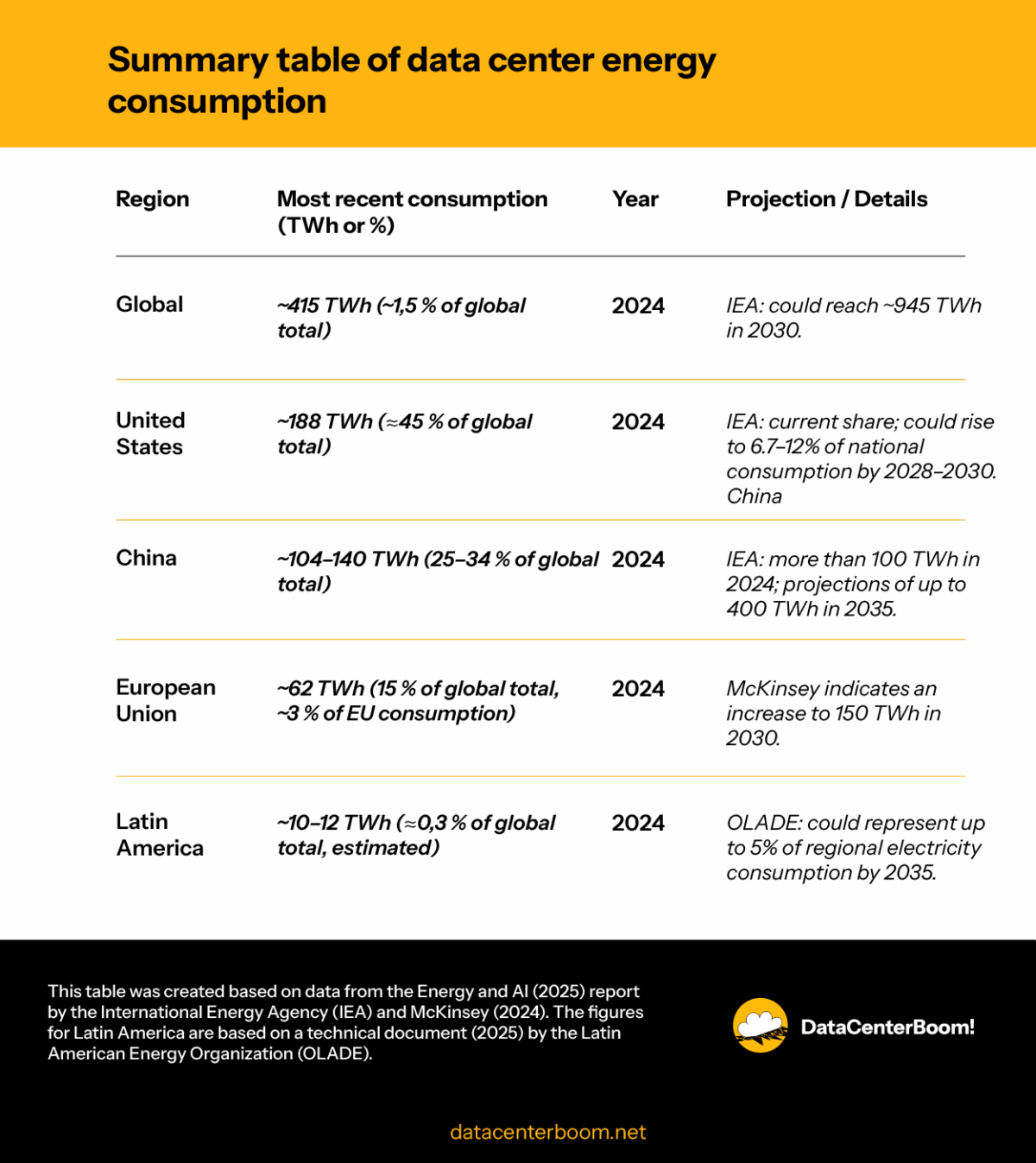

Data centers consume more and more energy, first because there are increasing numbers of them worldwide, and second because, driven by AI, the computing tasks they need to perform require a lot of energy. In fact, the International Energy Agency (IEA) released a report called Energy and AI (2025), which reveals several important facts about energy use, including:

- Data centers accounted for around 1.5% of global electricity consumption in 2024, or 415 terawatt-hours (TWh).

- The United States accounted for the largest share of global electricity consumption by data centers in 2024 (45%), followed by China (25%) and Europe (15%).

- Globally, data center electricity consumption has grown by around 12% annually since 2017, more than four times faster than the rate of total electricity consumption.

- Data centers focused on AI can consume as much electricity as energy-intensive factories, such as aluminum smelters, but they are much more geographically concentrated. For example, nearly half of the data center capacity in the United States is concentrated in five regional clusters. The sector accounts for a substantial share of electricity consumption in local markets. By the end of the decade, the US will consume more electricity for data centers than to produce aluminum, steel, cement, chemicals, and all other energy-intensive goods combined.

- Thanks to a digital economy where AI plays an increasingly important role, data center electricity consumption is expected to more than double to around 945 TWh by 2030. This is slightly higher than Japan’s current total electricity consumption. The report’s baseline scenario predicts that global data center electricity consumption will increase to around 1,200 TWh by 2035.

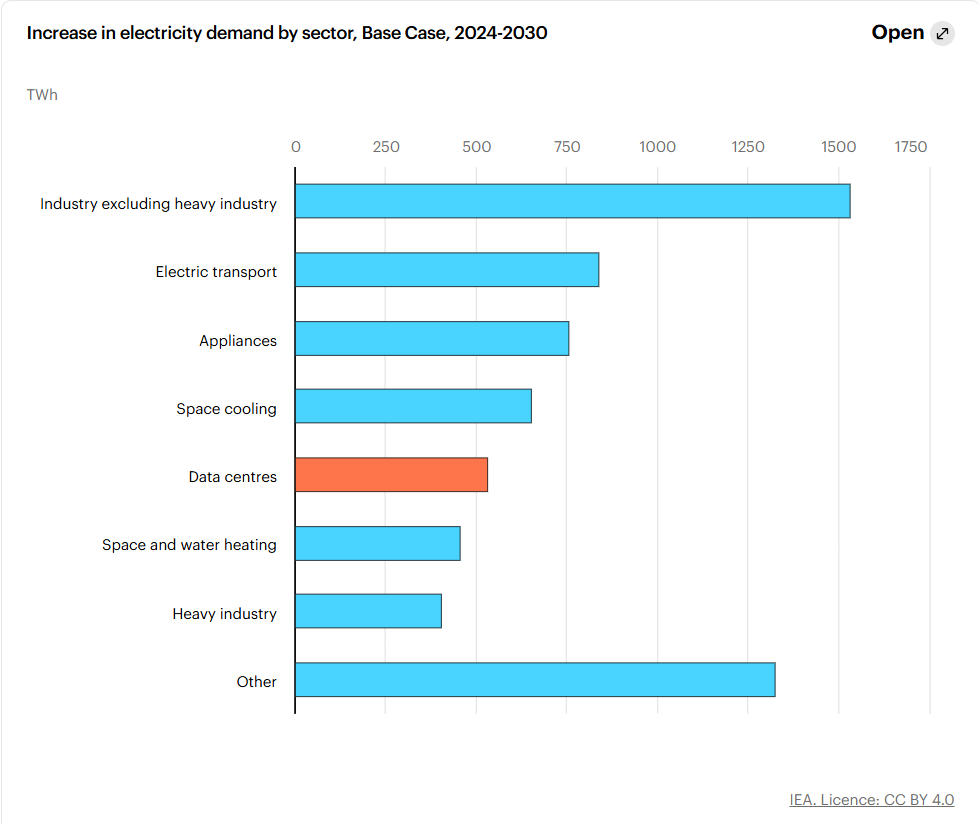

Nevertheless, in the same report, the IEA states that, despite the sharp increase, the growth in electricity demand from data centers accounts for less than 10% of global electricity demand growth between 2024 and 2030 in the baseline scenario. Other key factors, such as growth in industrial production and electrification, the deployment of electric vehicles, and the adoption of air conditioning, lead the way.

However, although the overall growth might seem smaller, the key point—which is repeatedly highlighted in the report—is that data centers, unlike electric vehicles, tend to be located in specific areas, making their integration into the grid potentially more challenging.

It is important to note that we are constantly dealing with highly uncertain scenarios: the same agency has said that, concerning models such as DeepSeek that require less than 10% of the energy used by other large AI models, the electricity demand of data centers may be overestimated, which contributes to the uncertainty (Financial Times, 2025).

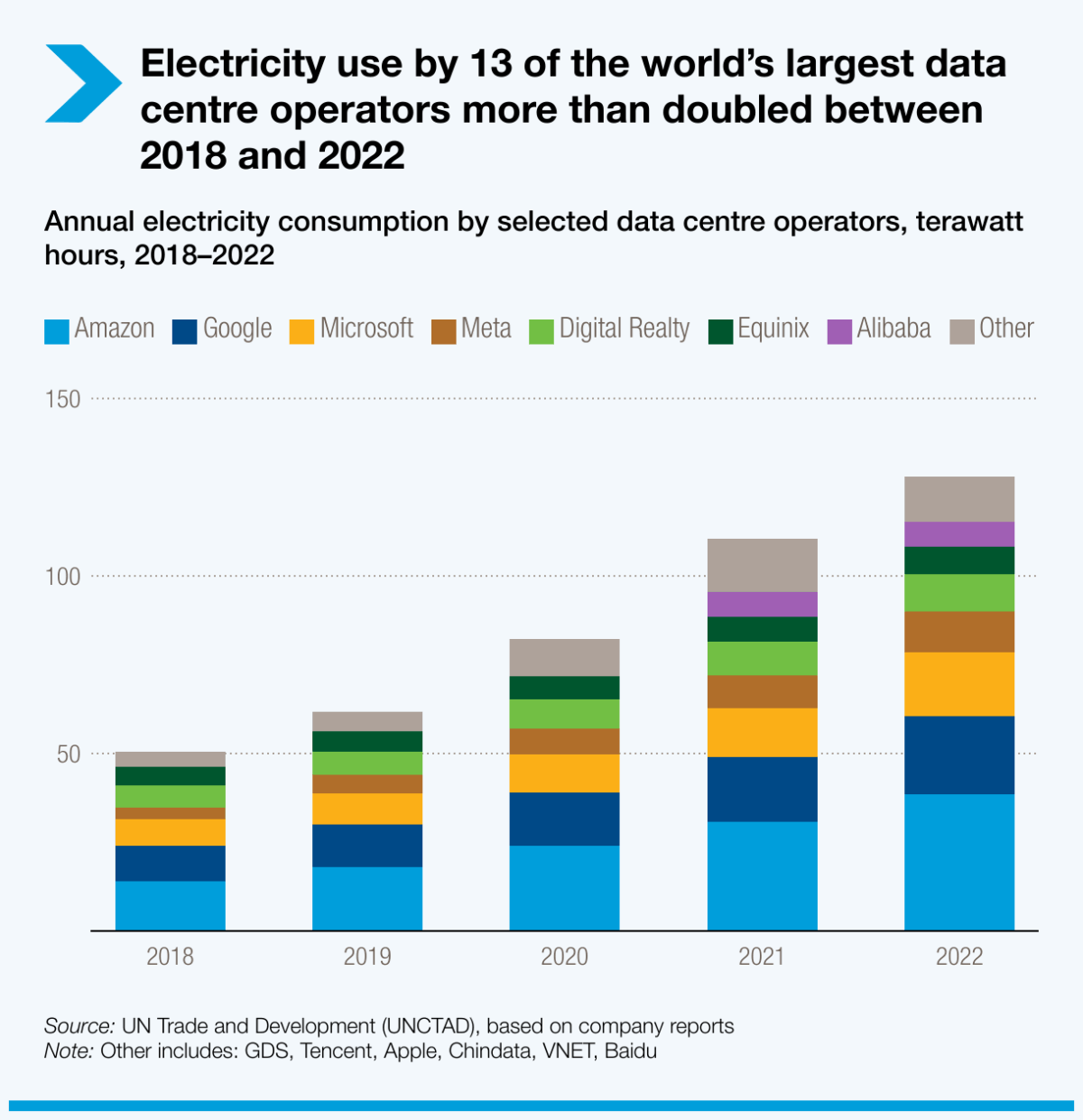

The actors behind this growth in energy demand are also important. The Digital Economy Report (2024) by UNCTAD (United Nations Conference on Trade and Development) notes that between 2018 and 2022, the electricity consumption of 13 large data center operators more than doubled, highlighting the urgency of addressing their high energy demand (along with their water footprint).

So, what are the socio-environmental impacts of this growing energy demand? Below is a list of those that seem to be receiving the most attention so far:

- Increased demand for fossil fuels and its effects on climate and health

Data centers measure their greenhouse gas emissions across three scopes: direct (Scope 1) emissions; indirect (Scope 2) emissions from the energy they consume; and indirect (Scope 3) emissions from their production supply chain. The most concerning information is from Scope 2.

In the context of Scope 2, the International Energy Agency (IEA) report “Energy and AI” notes that in 2024, more than half of the electricity consumed by data centers came from fossil fuels: about 30% from coal and 26% from natural gas. The rest of the electricity supply was split between 27% from renewable energies (mainly wind, solar photovoltaic, and hydro) and 15% from nuclear energy.

Coal and natural gas will remain essential in the short term, accounting for more than 40% of the increase in electricity demand through 2030. After that date, small modular reactors (SMRs) are expected to come online, providing low-emission baseload power. This, together with increased penetration of renewables, will enable a reduction in coal use in data center electricity supply by 2035.

However, the fact that half of the energy needed by data centers comes from fossil fuels means, in practice, two serious immediate consequences:

a. More global warming

Overall, UNCTAD’s Digital Economy Report (2024) emphasizes that the information and communications technology sector—which includes digital devices, networks, and data centers—was responsible for between 0.69 and 1.6 gigatons of CO₂ in 2020, equivalent to approximately 1.5% to 3.2% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This range places the digital sector in a category comparable, for example, to air or sea transport in terms of carbon footprint.

In the United States, according to the Environmental and Energy Study Institute (2025), emissions from data centers have tripled between 2018 and 2024, rising from 31.5 million tons to 105 million in 2023—a 300% increase—along with the significant growth in the number of facilities, from 418 to 5,381. Additionally, Jha et al. (2024) use AI models to estimate that the growing use of data centers could raise CO₂ emissions in the US by 0.4% to 1.9% by 2030, accounting for between 3% and 14% of emissions from the electricity sector. In Europe, a study by Beyond Fossil Fuels (2025) indicates that the expansion of data centers, driven by the growing sophistication of AI, could raise emissions by eightfold if electricity is sourced from fossil fuels. Under this scenario, the electricity demand would rise to 287 TWh/year by 2030, and emissions from new centers could grow from 5 million tons of CO₂ in 2025 to about 39 million in 2030. If accumulated over the next six years, the new data centers could release 121 million tons of CO₂ equivalent. This is equivalent to half of Germany’s planned CO₂ reduction across all sectors by 2030. They conclude:

“The additional electricity demand from data centers must be met with renewable energy, not fossil fuels, to avoid exacerbating the climate crisis. But if new data centers consume the renewable energy already planned for other sectors of the economy, the result will be to slow down the efforts of these other industries to decarbonize, which will increase emissions.”

Indeed, globally, the IEA estimates that emissions associated with data center electricity consumption will peak at around 320 million tons in 2030, before falling to around 300 million tons by 2035 in its baseline scenario. Although this represents only about 1% of global emissions from energy combustion, it is one of the few sectors where emissions are expected to increase over the next decade, along with road transport and aviation. In a scenario of greater growth in artificial intelligence (“Lift-Off Case”), emissions could account for up to 1.4% of the global total in 2035.

Emissions from emergency generators

Due to the AI demands in data centers, diesel generators, long considered a reliable fail-safe solution, are becoming even more essential, not just as a temporary measure in emergencies, but as a crucial component of a broader energy strategy. The challenge is that the power grid can no longer keep pace on its own. As a result, the industry is turning to complementary solutions, such as diesel generators with proven resilience and other systems that operate alongside the grid in normal situations, while ensuring that emergency diesel remains ready to fulfill its primary role (Dierksheide, 2025).

While a smaller data center may house only a few backup generators, larger projects, including those built to power AI, may have dozens. For example, Quantum Loophole’s Aligned Data Centers proposed installing 168 diesel generators capable of supplying 504 MW of power.

These diesel generators can be enormous, with power ratings ranging from 1.5 MW to over 3 MW each. Most generators are designed to provide between 1.5 and 2 times the total connected load. These generators emit significant amounts of particulate matter (PM), nitrogen oxides (NOx), sulfur dioxide (SO₂), and carbon dioxide (CO₂), pollutants that degrade air quality, contribute to climate change, and pose serious health risks to nearby communities.

However, these power generators must be tested regularly to ensure they will function when the primary power grid fails. A single 2.5 MW generator, during 100 hours of annual testing, can emit more than five metric tons of NOₓ and 0.3 tons of particulate matter (PM10), in addition to consuming around 50,000 liters of diesel and producing nearly 130 tons of CO₂. These tests, which are usually conducted monthly and accumulate 50-150 hours per year, contribute significantly to local air quality problems by releasing NOₓ, PM, and other pollutants (Eslami, 2025).

There is an interesting case in Mexico where emergency generators are not used for testing or outages, but rather because the power grid is not yet ready to meet their demand. Thus, a Microsoft data center in Colón, Querétaro, was unable to connect to the national power grid and therefore operates partially with gas generators. The company has admitted to using generators that could cover up to 70% of a data center’s consumption during certain hours, resulting in CO₂ levels equivalent to those of tens of thousands of homes (2025). These generators also pose additional risks related to the storage of large volumes of diesel fuel—between 10,000 and 50,000 liters per generator—which can lead to spills or leaks, contaminating soil, water, and air, and requiring costly remediation efforts (Eslami, 2025).

b. Increased air pollution and its impact on the health of the most vulnerable communities

This increase in electrical capacity is hindering countries’ renewable energy goals, such as those of the United States. To meet demand, energy service companies have increasingly turned to fossil fuels (Scope 2 emissions) that cause air pollution. This, along with backup diesel generators that power data centers when the electricity supply is disrupted (Scope 1 emissions), emits dangerous pollutants such as nitrogen oxides and fine particulate matter, increasing rates of respiratory and cardiovascular disease and raising the risk of cancer in nearby communities.

Using data from environmental permits and tools from the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Business Insider (2025) estimates that the public health impacts linked to this pollution in the United States currently amount to between $5.7 billion and $9.2 billion per year, including between 190,000 and 300,000 asthma episodes and between 370 and 595 premature deaths annually. In addition, backup generators alone contribute about 2,500 tons of nitrogen oxides per year, which could lead to 20,000 additional asthma cases and cost $385 million in public health expenses.

The report also shows that about 20% of data centers are located in communities already facing high environmental burdens, which worsens health inequalities: children have a greater likelihood of asthma and higher rates of premature births.

A 2025 study by the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative (EDGI) reaches similar conclusions. Specifically, the study focused on air pollutants associated with diesel exhaust (used in backup power generators) and emissions from other on-site generators, such as xAI’s gas turbines, which also emit NO2.

Among its findings are that:

- Communities living in proximity (i.e., one mile) to EPA-regulated data centers have higher air pollution burdens compared to the national median (i.e., the 50th percentile of air pollution).

- In particular, communities of color within one mile of EPA-regulated data centers face worse air pollution than other communities near data centers and the typical (median) community in the country. These trends are relatively consistent, but not as pronounced when state-specific averages are considered.

What will happen in the future? In 2024, Han et al. published The Unpaid Toll: Quantifying the Public Health Impact of AI, which describes how artificial intelligence data centers in the United States impact public health through air pollution. To do this, they used a life-cycle model that includes direct emissions from backup diesel generators, as well as the electricity consumed by data centers and the manufacturing of the hardware that equips them. Their conclusions are alarming:

- In terms of the daily operation of data centers, the study estimates that by 2030, emissions associated with their electricity consumption could cause around 1,300 premature deaths each year and more than 600,000 asthma episodes, with healthcare costs exceeding $20 billion annually. These figures place data centers at a level of harm comparable to that of highly polluting industries, such as coal-fired steel production, or even the vehicle fleet of a large state like California.

- The article also analyzes the training of large-scale models in these centers, such as Llama-3.1, whose electricity consumption is equivalent to the polluting emissions of more than 10,000 round-trip cars between Los Angeles and New York. According to the authors, the healthcare costs associated with this type of computational load may even exceed the economic cost of the electricity used.

- More importantly, the impact is not evenly distributed. The authors point out that communities near large clusters of data centers—often with fewer economic resources—could face per capita health burdens up to 200% higher than other less exposed areas. This reflects how the geographic concentration of data centers amplifies social and environmental inequalities.

2. Increased demand for renewable energy: myth and conflicts

The IEA projects that, between 2024 and 2030, renewable energy will account for about half of the growth in electricity demand from data centers. This is due to the rapid expansion of new renewable plants, the signing of power purchase agreements (PPAs) by large technology companies, and the trend toward locating data centers near wind and solar farms.

Therefore, renewable energy generation is projected to increase by over 450 TWh to meet data center demand through 2035, driven by short delivery times, economic competitiveness, and technology companies’ procurement strategies.

For this agency, the technology sector is helping to develop new nuclear and geothermal technologies. Nuclear energy contributes approximately the same amount of additional generation to meet data center demand, especially in China, Japan, and the United States. The first small modular reactors are expected to start operation around 2030.

The information provided by this agency must be analyzed with several crucial contextual elements in mind, especially the socio-environmental impacts of this week of renewable energy on reality.

a. Data centers increase renewables, but also fossil fuels!

The big question is whether future estimates that data centers will be powered mainly or exclusively by renewable energy are accurate. For now, this is speculative: uncertainties remain about what the energy landscape will look like in the future, especially since little is known yet about how AI technology and the market will evolve.

But one factor often missing from the discussion is that, in general, the increase in renewable energy has not necessarily replaced fossil fuels. Instead, both energy sources have combined to fuel growing demand from companies such as technology firms. The International Energy Agency (IEA) itself states in its Global Energy Review (2025) report:

“The latest data show that global energy demand grew at an above-average rate in 2024, resulting in increased demand for all energy sources, including oil, natural gas, coal, renewables, and nuclear power. This growth was led by the electricity sector, where demand grew at almost twice the rate of overall energy demand due to increased demand for cooling, higher industrial consumption, the electrification of transport, and the growth of data centers and artificial intelligence.”

Furthermore, it notes that the rapid deployment of five key clean energy technologies—solar photovoltaics, wind power, nuclear power, electric cars, and heat pumps—was not enough to halt the rise in global emissions, which have increased by 1.3 Gt of CO₂ since 2019.

While these technologies have initiated a structural slowdown in energy-related CO₂ emissions (together, these technologies now avoid around 2.6 Gt of emissions per year, equivalent to 7% of global energy-related CO₂ emissions), if energy demand continues to grow rapidly driven by data centers and AI, the energy transition will continue to lag: first, because the gap that clean technologies must fill will continue to grow, and second, because it is still cheaper to meet the increase in demand with fossil fuels.

In fact, the huge energy demand from data centers presents a perfect opportunity to develop new fossil-based projects. In Ireland, concerns have been raised about the justification for energy demand from data centers and the expansion of transition fuels such as natural gas (Brodie, 2024). A January 2025 report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) warns that the projected expansion of electricity demand by data centers is driving significant construction of fossil fuel infrastructure (gas plants and pipelines) in southeastern US states, which clearly hinders the energy transition.

Could there be an unusual deployment of renewable energy in the coming years that would allow them to gain ground in meeting the energy demand of data centers? For a variety of reasons, this seems unlikely (costs, technological competitiveness, obsolete network infrastructure, political volatility in countries such as the United States, direct or indirect subsidies for fossil fuels, etc.).

The viability problems of data centers with 100% local renewable energy

According to research on data centers (2025) by the Brazilian Institute for Consumer Protection (IDEC), it still does not seem reasonable to operate a large-scale data center solely with renewable sources.

Data centers can generate their own renewable energy (self-generation), obtain it from a nearby plant (co-location), or purchase it from an external supplier on the market or through a power purchase agreement. In the case of a data center powered solely by local renewable energy, the real-time balance between supply and demand is a challenge that must be taken into account: I) the needs of data centers for a highly reliable energy supply to maintain their quality of service; II) fluctuations in their load, which can be large between peak and normal behavior; and III) the variability, intermittency, and non-dispatchable properties of renewable energy generation.

For a large-scale data center to operate solely on renewable energy, energy storage devices, i.e., batteries, are essential. And batteries are expensive, which is one reason most companies opt for more stable energy sources, such as fossil fuels.

b. A digital transition designed for data centers, not people

It has been suggested that the solution to the carbon footprint would be for data centers to be powered 100% by renewable energy. Furthermore, both corporations and governments claim that the energy demand of data centers is an opportunity to accelerate the energy transition.

The signs, however, are not so optimistic.

In countries such as Ireland (by far the preferred European country for data center installations), the state promotes Corporate Power Purchase Agreements (CPPAs) to facilitate the energy transition. These are direct pricing agreements between companies and energy suppliers. This means that companies receive a guaranteed (low) rate on their energy costs directly from the energy supplier. It also means that new renewable energy does not reach households but goes directly to energy-intensive corporate infrastructures. These are not investments but rather corporate contracts implemented through the public grid, allowing a company to effectively monopolize future renewable energy capacity by leveraging public infrastructure.

According to the state’s argument, demand will influence supply: if companies need renewable energy, more will be built, thereby changing the grid’s energy mix. “As expected,” say Brodie & Bresnihan (2021), “they are also promoted by the technology industry, which allows them to present themselves as the solution to a problem (energy/climate) for which they are partly responsible.” However, for these authors, these infrastructures function as “energy vacuums,” that is, they demand massive amounts of electricity and absorb new renewable capacities through direct contracts. This distorts the energy transition because, instead of serving local communities and industries, much of that renewable capacity is dedicated to maintaining private digital infrastructure (Brodie, 2024).

Additionally, as the movement for a fair energy transition has historically denounced, the social and ecological costs of renewable energy generation projects are paid for by the communities that have contributed least to the climate and environmental crisis, for example, by displacing indigenous communities from lands that are now photovoltaic or wind energy fields. In the case of Brazil, this socio-environmental conflict is compounded by the fact that, in the same indigenous territories where wind turbines are being erected, the companies generating this energy are now seeking to attract their best customers, data centers, to set up there to save on transmission and distribution line costs, which has already raised alarms in the Anacé indigenous community in Ceará (2025).

In both examples, there is a logic of “green substitution” (fossil fuels for renewables), where green energies appear to legitimize technological expansion by reinforcing the inevitability of technocapitalism. This process reproduces spatial inequalities, favors corporate interests, and undermines environmental justice, as the social and ecological costs fall on rural areas (Brodie & Bresnihan, 2021).

c. Distortion of Big Tech’s actual carbon footprint

The ecological footprint of data centers remains hidden, obscured mainly by high-level corporate promises and selective transparency in their sustainability reports. That is why it is essential to interpret the latter carefully.

For example, technology companies such as Microsoft and Google acknowledge that they have alarmingly increased their electricity consumption, yet they also show a decrease in emissions. This is mainly because they factor in corporate renewable energy certificates and power purchase agreements.

According to an analysis by The Guardian (2025), from 2020 to 2022, the actual carbon emissions from Google, Microsoft, Meta, and Apple’s internal or company-owned data centers are likely to be around 662% higher than officially reported. This is because, despite widespread criticism, these technology companies continue to include renewable energy certificates (RECs) in their reports.

These are certificates that a company purchases to demonstrate that it is acquiring electricity generated by renewable energy to cover part of its electricity consumption; however, the catch is that the renewable energy in question does not have to be consumed by a company’s facilities. Instead, the place of production can be anywhere, from a city to across the ocean. Tech companies are the largest buyers of RECs worldwide (2024), and their continued use of these carbon credits could have far-reaching implications as more corporations seek to reduce their carbon footprint.

Obfuscation through complexity: the environmental reporting strategy of Big Tech

Researcher Thomas Le Goff (2025) recommends analyzing Big Tech sustainability reports by location, which reflects the carbon intensity of local electricity grids where energy is actually consumed. This approach avoids distorting Scope 2 emissions figures through REC strategies. When examining Microsoft and Google’s reports from 2020 to 2024, “Microsoft’s location-based scope 2 emissions more than doubled in four years, rising from 4.3 million metric tons CO₂ in 2020 to nearly 10 million in 2024. Google’s climbed from 5.8 million to over 11.2 million metric tons CO₂ over the same period.”

Similarly, Scope 3 emissions—which account for the carbon costs across a company’s entire value chain—are also understated in these reports. Neither company discloses “enabled emissions,” meaning the carbon released through the downstream use of AI tools, such as those deployed in oil exploration or logistics optimization.

Therefore, if market-based Scope 2 figures are replaced with location-based ones and full Scope 3 emissions are included, “Microsoft’s actual emissions in 2024 would be around 25.2 million metric tons CO₂, not the 15.5 million they report. Google’s total emissions would reach 23.4 million, not the marketed 15.2 million.”

Le Goff argues this is not greenwashing, since the reports contain valuable, often independently verified information, and the companies are making real investments in decarbonization and water management. Yet, this is a case of obfuscation through complexity: selectively reported figures, accounting methods that support preferred narratives, and a persistent gap between environmental marketing and environmental substance. As a result, sustainability accounting remains structured so that companies can present an idealized public image while relegating less favorable realities to appendices and footnotes.

3. Power failures due to electricity demand from data centers

Pressure on the electrical infrastructure is a growing concern. As demand for data centers increases, local grids face new stresses: insufficient capacity can lead to degraded power quality or frequent blackouts in nearby residential areas (Ngata et al., 2025; Chen et al., 2025).

More precisely, a Bloomberg report (2025) analyzes new evidence suggesting that AI data centers are distorting the quality of electricity delivered to US households, increasing the risk of appliance damage and fires. The proliferation of data centers supporting AI applications is putting unprecedented pressure on the power grid infrastructure, ultimately affecting the quality of power supplied to millions of consumers, especially in large data center markets such as Northern Virginia.

The problem, known as “harmonics,” occurs when the normal flow of electricity, which is in constant waves, is disrupted, causing erratic voltage spikes and drops. If left unaddressed, sudden surges or drops in power supply can cause sparks and even house fires. Analysis of the report showed that more than three-quarters of highly distorted power readings in the US are located within 50 miles of significant data center activity. New facilities adjacent to major US cities have exacerbated this situation, further overloading the power grid.

In Mexico, research by N+Focus (2025) found documents from the National Energy Control Center (Cenace) warning in 2023 that peak energy demand, combined with new requests, exceeds installed capacity, putting the guarantee of a quality electricity supply at risk. The same report warns of the impact of data centers on the Querétaro power grid, predicting overloads.

According to the media outlet, the impact has already begun in Querétaro. CENACE recorded more than 300 power failures nationwide between 2021 and 2023, most occurring in Querétaro and Guanajuato. Reports from the same media outlet have noted blackouts and power cuts since at least 2023. The industry, for its part, claims that 35% of its investment will go toward improving the power grid. However, it does not provide data on how many projects it has funded. Reports accessed by N+Focus indicate that tech giants are also affected by energy problems. At least five data centers did not start up or shut down due to a lack of connectivity.

The cyber risks of AI data centers

Chen et al (2025) warn that AI data centers not only have physical electrical impacts, but also pose emerging cyber risks to the electrical system.

Their concentrated demand, dependence on programmable power electronics, and connection to cloud architectures increase vulnerability. Coordinated intrusions could manipulate load scheduling or switch their Uninterruptible Power Supply (UPS) systems, inducing sudden demand changes of hundreds of MW. This can threaten frequency stability, overload local networks, or cause cascading failures.

For example, in 2024, researchers reported an incident at the “Alley Data Center” in Virginia, where 60 out of more than 200 data centers were disconnected following a protection system failure. This sudden disconnection shifted the load to local generators, creating an imbalance that required the utility to curtail generation in order to prevent a cascading failure. While not caused by a malicious attack, the event clearly illustrates how rapid load changes can expose vulnerabilities in the electrical system.

4. Energy justice and equity in question

Energy justice aims to achieve equity in social and economic participation in the energy system and to address the social, economic, and health burdens disproportionately imposed by it. There are several examples of how this principle is questioned when examining government public policy efforts to meet the energy demands of data centers.

Arizona has become one of the fastest-growing data center hubs in the United States. However, this rapid expansion raises concerns about its impact on disadvantaged communities that lack access to basic electricity. While state tax incentives attract data center developers, their proliferation increases pressure on Arizona’s electricity grid, leading to decisions that disproportionately affect vulnerable populations. In 2024, the Arizona Corporation Commission approved funding for infrastructure improvements to support the growth of data centers. Meanwhile, the commission rejected a separate proposal to expand electricity access to parts of the Navajo Nation, citing concerns about potential costs to consumers. As a result, thousands of Navajo households remain without electricity (2023).

Meanwhile, in Brazil, as technology companies expand their energy-intensive infrastructure, more than 1.3 million Brazilians live without electricity, especially in rural areas. Experts warn that the high water and energy consumption of data centers could overload Brazil’s power grid, increasing the risk of blackouts and raising energy costs for consumers. Elaine Santos, a researcher on energy poverty at the University of São Paulo, believes that technology companies must consider the local effects caused by their growing share of the country’s energy supply: “If they are going to build data centers where people don’t even have access to electricity, companies must offer compensation,” she argues. “Given that Brazil is being sold off, the compensation must be substantial” (2025).

5. Electricity rates rise for ordinary users

The Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) published a series of reports in 2025 analyzing the energy demands of data centers and AI in the United States. All highlight a central warning: the rapid growth of data centers is forcing the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure (such as gas power plants, gas pipelines, and transmission lines) that is likely to be oversized. As a result, these investments do not always respond to real or proven demand but rather to inflated projections. The danger is that consumers will end up paying for unnecessary infrastructure, which could slow down the transition to clean energy.

This occurs because the regulatory and electricity market system in the US—and in particular the PJM Interconnection (the largest regional transmission operator in the United States)—works in a way that makes the costs of oversized infrastructure inevitably fall on consumers.

Indeed, in its June 2025 report, the IEEFA warns that utilities’ projections for AI demand are up to 50% higher than the technology industry’s own estimates. If these investments in oversized fossil fuel infrastructure are made, the regulatory model (including PJM in its region) ensures that the costs are passed on to consumers, even when they are never justified.

For example, in the southeastern United States, electric companies justify new gas plants and pipelines based on the supposed demand from data centers. In January 2025, the IEEFA warned that even if that demand does not materialize, regulations allow investments to be recouped through electricity rates, so consumers end up paying for unnecessary infrastructure.

Another criticism is the function of PJM’s “capacity market” (a mechanism designed to ensure committed generation capacity in the future), which has driven prices higher amid expectations of a data center boom. In two years, prices increased nearly tenfold. And even if that demand has not materialized, market prices are already being passed on to consumers’ bills because PJM compensates generators for their future availability.

Similarly, a study by Carnegie Mellon University and North Carolina State University (2025) indicates that electricity rates could increase by an average of 8% in the United States through 2030 due to higher demand from data centers and cryptocurrency generation. They conclude that the growth of digital infrastructure is outpacing the electrical system’s responsiveness. Data centers offer potential benefits, but they risk higher emissions and higher prices for households if proactive, coordinated planning is not implemented. Policymakers must act now to adapt infrastructure investment and regulation to this increasing demand.

More specifically, in May, the IEEFA (2025) analyzed how this is also a distributional problem: PJM’s cost allocation model means that West Virginia customers will cover more than $440 million in transmission lines that primarily benefit data centers in Virginia. In other words, those who do not receive direct benefit are financing infrastructure driven by the policies of another state.

6. Noise pollution in neighborhoods

Data centers generate significant noise pollution, primarily from diesel generators and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) systems.

Data centers have long been noisy places, but they are becoming even noisier as companies find ways to pack ever-increasing densities of equipment into them and expand the power and cooling systems needed to support that equipment.

The most significant sources of noise pollution are:

- Cooling systems

Most of the system is inside the facility, while some HVAC fans are outside. With increasing demand for AI and data storage, servers consume more energy every day. Temperatures rise faster when servers have heavy workloads, so HVAC systems run continuously at higher rates to cool the servers and aisles. - Energy consumption and the power grid

Constant high-power consumption causes a low-frequency humming sound. Added to this are the noises generated by the high-voltage towers that power data centers.

The consequences for health and the environment are increasingly being observed, especially in areas where they are concentrated. These include:

a. Potential hearing damage to data center personnel

To put noise levels in context, safe sound levels are 70 A-weighted decibels (dBA) or lower, according to the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Exposure to sounds of 85 dBA and above can harm hearing. Noise levels inside a data center can reach 96 dBA (Mahan, 2024). Exposure of more than half an hour could cause hearing damage.

Noise levels are higher inside a data center because the enclosed space echoes the hum and buzz of server fans, HVAC systems, and other equipment. Data center staff who are exposed to high noise levels for extended periods may experience hearing damage, reduced productivity, and increased stress.

b. Health issues in communities

People living near data centers report health issues caused by noise pollution. As with data center staff, the constant humming or buzzing in data centers can lead some individuals to experience headaches, stress, and sleep problems. Lack of sleep and stress can result in anxiety, cognitive difficulties, and increased cardiovascular risks. In more severe cases, noise pollution may cause tinnitus and hearing loss. Children are especially vulnerable (Fairfax Station Connection, 2023; Campbell, 2025).

c. Effects on wildlife

Noise pollution also impacts wildlife. Just as boat engines and sonar equipment affect marine life, land-based noise pollution interferes with animal communication and causes them to adopt new migration patterns.

Flora and fauna can be affected. In Fairfax County, just outside the Washington, D.C., beltway, the construction of a data center threatens the nesting grounds of blue herons, solitary water birds often seen in the shallow waters of local rivers and streams (Fairfax Station Connection, 2023; Campbell, 2025).

High-voltage towers in the spotlight

The high-voltage towers that power data centers have also been criticized by the communities affected by their location. In Latin America, analyzing protests in Chile (Huechuraba, Santiago de Chile) and Brazil (Fortaleza), it can be seen that one of the main concerns is the noise pollution they generate and its impact on people and biodiversity, but also how their presence destroys natural and culturally relevant spaces and makes them even more unsafe (Moreno, 2023; Globo, 2025).

Part 2. Fresh water consumption and its consequences

Water consumption in data centers is very similar to energy consumption and carbon emissions. As data centers use more energy for regular operations and to support AI, they consume more water to cool their processor chips, preventing overheating and potential damage. Similarly, as energy consumption in data centers increases, so do carbon emissions.

There are two key concepts of water use (Pengfei Li et al., 2025): extraction, the total amount of water taken from a source, and consumption, the portion that evaporates and does not return to the system. In many data centers, between 45% and 60% of the water extracted is consumed. However, estimating this globally is challenging because many facilities do not publish water usage data.

According to a special report by J.P. Morgan x ERM (2024), a medium-sized data center consumes approximately 300,000 gallons of water per day (110 million gallons per year), equivalent to the annual water consumption of approximately 1,000 households. Large data centers (so-called hyperscale centers common to Big Tech services) can use between 1 and 5 million gallons of water per day, comparable to the amount used by a city of 10,000 to 50,000 people.

Thus, their rapid expansion threatens freshwater supplies because extracting water from local streams or underground aquifers can lead to aquifer depletion, especially in areas with water scarcity. Below are some of the resulting socio-environmental impacts:

1. Direct use of fresh water in drought-stricken areas

According to J.P. Morgan x ERM (2024), U.S. data centers used more than 75 billion gallons of water in 2023. For researchers such as Shaolei Ren and Amy Luers (2025), scope 1 water consumption (which occurs in the operation of the data center itself) at the national level might seem relatively modest, but that isn’t the real issue. The key point is that in the U.S., data centers are concentrated in regions already facing water shortages, and the strain on local water supply systems can be significant.

In fact, 20% of the water currently consumed by data centers in that country comes from watersheds that are already experiencing water stress, posing a risk to the technology industry, surrounding communities, and the environment (J.P. Morgan x ERM, 2024).

Since data centers often cluster in certain geographic regions, the combined effect of multiple facilities on local and regional water supplies is significant. However, very little is understood about this impact, especially in areas already experiencing water stress.

A study by Ceres (2025) focusing on Phoenix, Arizona (USA), reports that the region is experiencing water stress while also being a rapidly growing city and a booming data center hub. There, the growth of data centers could increase pressure on water resources in already stressed basins by up to 17% annually. But beware, the biggest problem may not even be the total consumption of fresh water; it could be the timing of that consumption. On hot days, when residents and businesses need water most, data center water demand also skyrockets.

For Ceres, the high concentration of data centers in water-stressed regions could threaten the financial value of companies if not properly assessed and addressed, since water use and cumulative impacts can significantly affect water availability. The potential risk is compounded by the cumulative impacts of data centers on water resources, which may conflict with ongoing planning efforts to secure a sustainable water supply.

Although beyond the scope of Ceres’ analysis, it recognizes that cumulative impacts on water resources from the concentration of all water users should be given greater prominence in water management discussions. For example, the Phoenix region has experienced significant growth in semiconductor manufacturing, which requires large amounts of ultra-pure water.

2. The indirect water use of energy consumed by data centers

The other part of the equation is the electricity that powers data centers. If a data center operates on electricity from a thermal plant (coal, gas, nuclear), that plant uses water to cool its turbines or condensers. Although unseen, that water is part of the data center’s indirect water footprint (Scope 2). The U.S. electricity sector withdraws about 11.6 gallons of water and uses 1.2 gallons for each kilowatt-hour of electricity generated, making it one of the country’s largest water consumers. In many regions, this indirect use can account for up to 80% or more of the total water footprint (Shaolei Ren and Amy Luers, 2025b).

Power plant water is usually not drinkable and isn’t taken from city water supplies. Still, it can strain rivers, aquifers, and ecosystems, particularly in regions with limited water resources.

In most U.S. data centers, indirect use is significantly greater than on-site water use. One article (Pengfei Li et al, 2025) estimated that, in 2023, using GPT-3 chat to generate a single 150-300-word text would consume a total of 16.9 milliliters of water in an average US data center: 2.2 milliliters for on-site cooling and 14.7 ml for electricity generation. Improvements in subsequent models’ efficiency have likely reduced these figures, but indirect water use remains prevalent.

Thus, for authors such as Shaolei Ren and Amy Luers (2025b), the real water challenge posed by AI is not only the local water use in data centers, but also the reliance on an electrical system that, in many cases, consumes large volumes of water.

3. More fresh water use with the rise of AI

Nuoa Lei et al (2025) analyze how different types of workloads—including those associated with AI and intensive computing—differentially influence water consumption in data centers. They identify that the most demanding thermal power loads (such as those derived from training or inference of large models) require greater cooling measures, which increases water use in evaporative systems or auxiliary circuits.

For researchers such as Pengfei Li et al (2025), despite its profound environmental and social impact, the increase in AI’s water footprint has received little attention. For the authors, the rapid growth of AI models and data centers will significantly exacerbate global water stress, especially in regions already facing freshwater shortages. Therefore, it is imperative to consider the water footprint as a key sustainability indicator for AI, alongside carbon emissions. This has a clear correlation. According to researcher Masheika Allgood (2025), Google’s data centers in Europe are more efficient in their water use, not because of their cooling technologies, but because they are not primarily AI-focused. They are Google Cloud facilities that host more traditional workloads, which don’t require the same level of cooling needed for thousands of GPU racks that run and train large language models (LLMs) 24/7. In a post on her LinkedIn (2025), she stated:

“So if you think your water is safe because you’re in Europe, you are in for a rude awakening. Google is looking to trade on the goodwill they’ve built to expand all of their data center campuses with AI-specific facilities. The same hyperscale, massively consumptive AI data centers that we have in the US – that are sucking us dry. Wake up and smell the water scarcity before it’s too late.”

4. Water justice: community needs versus individual needs

Water justice is a concept that promotes the fair and equitable distribution, governance, and use of water resources, acknowledging water as a human right and an ecological necessity. It goes beyond simple access: it examines who controls water, who benefits from it, and who bears the environmental and social costs of its exploitation. Thus, to achieve water justice, it is essential to tackle historical and structural inequalities in political power, economic systems, and cultural recognition (Sultana, 2018).

A growing concern regarding the expansion of data centers is the unequal distribution of water rights, while rural and marginalized communities often face restrictions on water use or higher utility bills.

Especially in Latin America, many social and environmental controversies surrounding the installation of data centers center on the unequal use, control, and distribution of water. Conflicts arise not only for technical reasons—such as the amount of water they consume for cooling—but also because of what that use represents in contexts of scarcity, privatization, and historical inequality in water access.

A paradigmatic case occurs in Mexico and is extensively researched by N+Focus (2025). In 2015, Conagua, Mexico’s federal agency that regulates national waters, warned that four aquifers in the state of Querétaro were in water shortage and advised not to issue any more licenses. On the same day, the state government launched a plan to attract data centers to the region. But since no additional licenses were available, the data centers found two ways to get water.

The first approach was to purchase a share of the permits already issued, a common method in which a person with a water extraction license can sell part of their rights to another interested party. Microsoft does this in the Vesta industrial park, where it has a license to extract 25 million liters annually starting in 2023, according to Conagua documents accessed by N+Focus. The US company was granted a portion of an extraction permit owned by QVC, a commercial company linked to the Vesta industrial park, where Microsoft’s data center is located.

The second is to rely on the state government, which supplies them with water directly. This maneuver has been permitted by law since 2022, when the current governor, Mauricio Kuri, promoted new water regulations known as the “Kuri Law,” which was opposed by social and environmental organizations. This law allows municipalities and the state water agency to grant concessions, something previously reserved for Conagua. An example: N+ Focus accessed the feasibility request for drinking water services for Ascenty’s third data center, issued in May 2023. In it, the Querétaro government guarantees a maximum of one million liters of water per month. But the company argues that they use much less, claiming that the water they take from public facilities is only for human consumption. At least seven of the data centers installed in Querétaro applied for their permits a year earlier, in 2021.

As also noted in the N+ Focus report, Marco del Prete, current Secretary of Sustainable Development for the State of Querétaro, stated: “If a data center requires as much water as they say it does, they will not be installed in Querétaro. We would not have enough water to satisfy them. Querétaro’s water is for its citizens, for its families.” The reality is that almost 15% of households in Querétaro lack piped water, and water cuts are frequent in two out of ten households in the state, according to data from the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Inegi).

Beyond distributive injustice in water

IIn his analysis of water conflicts linked to the artificial intelligence value chain, Sebastián Lehuédé (2025) distinguishes between distributive injustice and ontological or elemental injustice. The former refers to the unequal distribution of water resources: who has access, how much is used, and who pays the environmental costs. The latter, on the other hand, points to a deeper level, where the conflict is no longer just about quantities or rights, but about how water is understood and treated by different social actors.

In communities affected by data centers or lithium mining in Chile, Lehuédé observes that water is not conceived solely as an economic resource but as a living and relational entity, fundamental to their way of life. When a technology or mining company uses it as a simple input to cool servers or extract minerals, it imposes a technocratic view of water that ignores its symbolic and vital dimension.

This imposition constitutes an injustice that not only deprives communities of physical water but also breaks their ontological relationship with the element, replacing a relational and spiritual conception with an instrumental and extractive one. For this reason, the author argues that water conflicts surrounding artificial intelligence and digital infrastructure cannot be resolved solely with technical or redistributive solutions.

Part 3. Increase in electronic waste and its dangers

Data centers are a major source of e-waste due to their continuous operation and high equipment replacement rates. Thus, in a data center, cables, batteries, uninterruptible power supplies (UPS), air conditioners (CRAC and CRAH), power distribution units (PDUs), and transformers are also periodically removed and discarded when warranties expire and units fail to meet the high standards of reliability and redundancy set by entities such as the Uptime Institute (González Monserrate, 2022).

In fact, a study by Veau et al. (2023) analyzes the growth of data centers in Germany and how this drives the generation of electronic waste. It models hardware flows based on installed capacity and estimates that data center equipment (servers and IT hardware) is typically replaced every 3 to 5 years. The study reveals that larger data centers generate more waste, while smaller ones are increasingly being replaced by larger facilities. It also points to the lack of sector-specific data to monitor formal collection and recycling of e-waste, which makes it difficult to design effective policies.

According to Andrews et al. (2021), data centers operate under a linear production model characterized by material extraction, intensive energy consumption, and rapid equipment replacement. This model has caused issues such as faster technological obsolescence, increased electronic waste, and the loss of critical materials such as copper, gold, rare earths, and lithium. For these authors, the sector lacks an integrated vision: the subsystems of design, construction, operation, maintenance, dismantling, and recycling operate in isolation, preventing a “whole system” approach to sustainability. As a result, the industry faces a structural contradiction: while it fuels global digitization, it reproduces dynamics of environmental unsustainability and industrial fragmentation that hinder any transition to a circular economy.

The persistent challenges of e-waste around the world

According to the Global E-Waste Monitor 2024 report (Cornelis P. Baldé et al, 2024), the world generated a record 62 million tons of electronic waste (e-waste) in 2022, representing an 82% increase since 2010. However, only 22.3% was formally collected and recycled in a documented manner.

E-waste generation is growing much faster than formal recycling capacity: the annual amount is estimated to increase by 2.6 million tons, leading to projections of up to 82 million tons by 2030. In addition, the documented collection and recycling rate is expected to decline slightly to 20% by 2030 due to the growing gap between generation and management capacity.

The report identifies several factors that exacerbate this gap: technological progress, growing consumption of electronic devices, shorter life cycles, limited repair options, designs that are not recycling-friendly, and insufficient e-waste management infrastructure in many countries.

Although 81 countries have e-waste legislation (as of 2023), effective implementation, collection, and recycling targets are scarce: only 46 countries have collection targets, and 36 have recycling targets. Meanwhile, the illegal trade in electronic waste persists, with undocumented movements of tons of e-waste from high-income countries to middle- and low-income countries.

The production of this electronic waste from data centers poses several socio-environmental risks, including:

1. Hazardous effects on health and the environment

Waste generated by digitization contains hazardous materials that, if not properly managed, can harm the environment and human health.

The main environmental hazards of e-waste stem from the heavy metals and persistent organic pollutants contained in devices (Kang Liu et al., 2023). During the treatment of electronic waste—for example, dismantling, separation, and informal recycling—these pollutants can be released into the air, soil, dust, water, and other media, and then transferred through geological and biological cycles.

Likewise, during the incineration of electronic components, the resulting gases (such as sulfur, nitrogen, and dioxins) and heavy metals become atmospheric pollutants. These can accumulate, transform, and migrate to living beings and human communities through media such as water, soil, or atmospheric dust.

But even with advanced dismantling processes, the pollutants generated during recycling are difficult to control due to the complexity of the materials involved and their persistence. Thus, recycling requires advanced technologies, as a significant portion of valuable raw materials is lost during fine separation, and pollutants can be released.

2. Differentiated socio-environmental and health impacts

Much of the e-waste generated today is not properly recycled: many devices end up in landfills or are exported to lower-income countries, where they are dismantled by hand, creating health risks from exposure to toxic substances such as lead and mercury (2024).

Furthermore, the most vulnerable populations, especially children and pregnant women, face elevated health risks. Contaminants can cross the placenta, affect neurological development in fetuses and infants, decrease lung function, and contribute to respiratory diseases, among other effects.

In addition, informal work in e-waste recycling (e.g., unregulated collection or dismantling) directly exposes many people, including children, to these chemical hazards (WHO, 2024).

Kang Liu et al. (2023) report a case of child exposure: heavy metal levels (Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni, As) in children from a population exposed to e-waste were, on average, 3.90 times higher than in children from a reference population (p < 0.01). They also cite a 2009 report from Guiyu, China, where the uncontrolled release of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) during recycling was a major source of accumulation in the human body.

3. More CO₂ emissions

The direct impact of electronic waste on climate change stems from the production of potent greenhouse gases (GHGs) during improper disposal. In many areas, improper handling practices are common, such as unregulated dumping in landfills and open-air burning of electronic waste (Fawole et al 2023).

For example, it is estimated that one metric ton of printed circuit boards can contain concentrations of gold minerals 40 to 800 times those of the gold mined in the United States. This density of precious metals, combined with the combustion process, can generate significant volumes of GHGs. In addition, refrigerants and insulating foams in waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE) contain hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), which are powerful GHGs. If not properly managed, they can be released into the atmosphere during disposal.

Furthermore, leachate from landfills where electronic waste is often deposited generally contains high levels of organic matter that decomposes to produce methane, a greenhouse gas 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat. Landfills contribute about 14% of human-caused methane emissions worldwide. Therefore, disposing of electronic waste is a significant source of greenhouse gas emissions, directly connecting electronic waste management to climate change.

In fact, between 2014 and 2020, embodied GHG emissions from e-waste generated by ICT devices increased by 53%, amounting to 580 million metric tons (MMT) of CO₂ in 2020. Without targeted interventions, emissions from this source are projected to grow to around 852 MMT of CO₂ annually by 2030 (Singh & Ogunseitan, 2022).

4. More electronic waste thanks to AI

How does the adoption of AI affect e-waste production from data centers? A recent study in the journal Nature Computational Science (Peng Wang et al, 2024) estimates that aggressive adoption of large language models (LLMs) could generate 2.5 million tons of e-waste per year by 2030.

The study outlines four scenarios for AI adoption, ranging from limited to aggressive use. Starting from a baseline of 2,600 tons per year in 2023, the aggressive scenario suggests a total of 5 million tons of e-waste between 2023 and 2030. The article points out that the study considers only large language models (LLMs) like generative AI, not other types of AI, which would raise the projected e-waste estimates.

Thus, the growth and proliferation of generative artificial intelligence could worsen the global issue of electronic waste. As companies deploy increasingly powerful hardware—for example, servers with specialized chips—the frequency with which this equipment becomes obsolete threatens to skyrocket computer replacement rates.

The deregulation of forever chemicals in data centers

The acronym PFAS stands for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. They are the most persistent synthetic chemicals known, which has led to them being nicknamed “forever chemicals.” The qualities that make them so sought after by industry are primarily their stability at high temperatures, their ability to repel water and grease, and their surfactant properties. These characteristics make them widely used in the data center industry, both in electronic components and in cooling systems.

There is evidence that exposure to PFAS can cause adverse health effects. These are linked to a weakened immune system, liver damage, increased cholesterol levels, decreased birth weight, kidney and testicular cancer, and endocrine disorders. They also decrease the immune system’s response to vaccination in children. Added to this is the indirect danger they pose through environmental degradation, as they will remain for a long time, even if releases were to stop immediately.

Recently, attention has focused on their presence in e-waste. PFAS are used in electronic devices because of their heat resistance, chemical stability, and repellent properties, which means that a variety of electronic products contain them in coatings, insulators, and sensitive parts. They are present in printed circuit boards, cable coatings, thin films, seals, and temperature-resistant components, among other items. PFAS can be released during the dismantling, recycling, combustion, shredding, and final disposal of this waste.

They are also present in data center cooling technologies, particularly in two-phase immersion systems and in fluorinated refrigerants or thermal fluids. In two-phase immersion systems, the fluid undergoes a phase change (evaporation/condensation) to absorb very high thermal loads, and these fluids are often PFAS-containing or related compounds. Although these gases may not be intentionally released, leaks, disposal, and degradation can result in the release of PFAS or their persistent derivatives, such as TFA (trifluoroacetic acid).

Recent studies indicate that, although liquid cooling (including immersion) can significantly reduce energy consumption, water use, and greenhouse gas emissions in data centers, such systems currently rely on PFAS to function. For example, a Microsoft study finds that immersion techniques could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 15-21%. Still, it warns that this system relies on PFAS, which face increasing regulatory pressure in both the European Union and the United States, potentially leading to future restrictions on this technology (Skidmore, 2025).

This latter restrictive scenario seems unlikely with Trump-style administrations. In the context of the “Great American Comeback” program, which is aligned with several executive orders by President Donald J. Trump aimed at accelerating investment in artificial intelligence, in September 2025, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) began prioritizing chemicals used in data center infrastructure to reduce “uncertainties that hinder investment and innovation” (Beeton, 2025).

However, Maria Doa, senior director of chemical policy at the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), says the EPA’s press release is revealing. “The administrator does not say that EPA will do a rigorous review as expeditiously as possible, but that it will ‘get out of the way. This clearly indicates that EPA will not conduct a rigorous review to determine if and how these chemicals can be used safely, but instead will put industry ahead of the health of workers and the public.”

Part 4. Pressures on land use and their consequences

Today’s data centers, with more than 40 megawatts, require an area slightly larger than five soccer fields and consume electrical power similar to that of 36,000 homes.

Generally, finding sites of this kind is very challenging and usually demands extensive initial work, such as installing high-voltage power lines, building new substations, relocating or removing existing easements or public utilities, or mitigating complex environmental risks on virgin land.

But these companies also require affordable land for infrastructure that powers their operations, such as electricity generation facilities, waste heat utilization facilities, transformer stations, underground telecommunications networks, electricity, heating, water networks, or waste disposal sites.

This pressure to acquire land has several consequences, some of which are discussed below:

1. Tensions in urban development

In cities where data centers are increasingly concentrated, especially those that require special features to support AI (primarily access to power, water, and connectivity), controversies have arisen because they compete with more urgent real estate needs, such as housing and retail stores.

For example, in Atlanta, USA, the uncontrolled construction of data centers makes it difficult for the city to address its housing shortage, which amounts to about 100,000 units in the metropolitan area. Residents, incidentally, share these concerns (Parker, 2024).

2. Rising land prices

AI data centers are large, energy-intensive facilities that often require access to extensive land to operate. As a result, especially in populated urban areas, there is a mismatch between land demand and supply. Many metropolitan areas are already constrained, forcing real estate developers to overpay for titled land or resort to secondary markets (Nelly, 2025, Datacenters, 2025).

In Northern Virginia, USA, which hosts many of the world’s largest data centers, land prices have increased over the past five years. For example, in Loudoun County, Virginia, the price of titled land has doubled in just two years due to intense competition. Texas, a state that already favors businesses, is experiencing similar trends as AI companies compete for land near power grids and fiber optic networks.

This change not only affects industrial land. Commercial areas surrounding the data center are experiencing increased demand for warehouses, offices, and service companies that support data center operations. Even residential areas near new AI centers are seeing price increases as workers relocate and communities expand. For real estate investors, tracking land acquisitions and upcoming AI projects could yield significant returns in emerging markets.

This trend could also drive significant upgrades to local power grids, influencing property values in areas that can support high energy consumption without interruption.

3. Eminent domain

Compulsory purchase refers to the power of the government to take private property for public use in exchange for compensation. This measure has long been a tool for developing various infrastructures. In the age of artificial intelligence, it is increasingly used to enable transmission lines that power data centers, whether from fossil or renewable energy sources (Turley, 2025).

For example, the Piedmont Reliability Project in Maryland is a proposed 70-mile, 500,000-volt transmission line designed to supply power to Northern Virginia’s “data center alley,” where AI servers are heavily concentrated. Residents denounce the project as “government land grabbing” that threatens farms, ecosystems like Gunpowder Falls State Park, and property rights, all for the benefit of out-of-state data centers (Condon, 2025).

Traditionally, high-voltage transmission lines in the US are financed through utility rates passed on to consumers, who pay through higher electricity bills. In Maryland, for example, residents are already facing skyrocketing costs due to energy imports and green policy failures, exacerbated by the demands of data centers (Turley, 2025).

4. Transformation of rural land use

The reasons behind the transformation of rural land into server centers are diverse, but the main ones are related to the availability of natural resources.

In Medina County (Texas, USA), Microsoft purchased plots of land that were previously cotton or corn farms and prepared them for the construction of new giant data centers. The same thing happened in Hutto, a city southwest of Austin, where 65 hectares of agricultural land are now being converted into a 67-hectare data center. In Presidio County, west of Texas and adjacent to the Mexican border, a plan is to build a 32,374-hectare mega data campus on cattle ranch land. However, there are still ranches in operation, so the initiative is being discussed with local authorities and the community (Guarneros, 2025).

In Querétaro, Mexico, most of these fields that were once used for agriculture or livestock are now unused, making them ideal for data centers. Additionally, agricultural land is often available in large, continuous blocks, unlike fragmented urban land, and is situated near electrical substations or transmission lines that power irrigation systems. In the case of Querétaro, they operate with the San Juan del Río Valley aquifer, which recorded a deficit of 56.8 billion liters in July (Guarneros, 2025).

5. Land grabbing and dispossession in favor of private interests

Land grabbing, often referred to as neocolonialism, is the takeover of land, sometimes on a very extensive scale, along with its natural resources. It is carried out by private or public actors, using different methods, whether legal or illegal. As a result, the land’s resources are commercialized. All of this happens at the expense of farmers’ interests, agroecology, food sovereignty, and human rights (Bludnik, 2022).

The objective of land grabbing is always the same: to obtain maximum profits for capital owners and financial intermediaries. However, regardless of the motives behind land grabbing, it is an emanation of the changes taking place in the modern world. These changes involve moving away from traditional small-scale farms based on labor and subsistence production for local markets. Instead, capital-intensive monoculture agricultural enterprises (such as data centers) are being established, depleting the environment’s finite resources and geared toward mass production for domestic, international, or global markets.

Socio-environmental conflicts over land grabbing and dispossession to favor the interests of the capital behind data centers are multiplying around the world.

In March 2022, Microsoft acquired land in the villages of Mekaguda (Telangana, India) and Shadnagar and Chandenvelly. The acquisition was managed by the Telangana State Industrial Infrastructure Corporation (TSIIC), which pooled the land and transferred it to Microsoft as part of the state’s industrial strategy. Shortly after the acquisition, residents began to raise objections. They allege that Microsoft has engaged in illegal occupation beyond the boundaries of the acquired land, that the project has caused pollution in Lake Tungakunta, and that access to communal paths used by residents for farming, grazing, and water collection has been lost. In July 2023, a group of 57 local residents filed a petition with the Telangana High Court against Microsoft, other companies, and state agencies. The petition demands that Microsoft and the involved companies stop the illegal occupation. The court admitted the petition, and legal proceedings remain open to date (September 2025) (Yarlagadda, 2025).

Meanwhile, in 2023, the planning and budget committee of the state of Querétaro, Mexico, approved a trust to develop CloudHQ’s $4 billion Colón data center campus, comprising six hyperscale data centers, with the first building scheduled for completion in 2026. As part of the trust, the state provided a 518,470-square-meter property worth $17.7 million, where the campus will be located (DCD, 2023).

Although these mechanisms were not particularly controversial at the time, recent critical reviews of the socio-environmental impacts of data centers in Querétaro have sparked renewed controversy. For example, on his Facebook page, current Congressman Gilberto Herrera Ruiz publicly described the trust measure for CloudHQ “dispossession,” alluding to the fact that “the government gave 50 hectares to a company for $1,000 pesos” (Herrera, 2025). More profoundly, Paola Ricaurte and Teresa Roldán (2025) analyze data center policies in the state of Querétaro and situate the expansion of data centers within a historical continuum of dispossession that dates back to the colonial invasion and the state’s subsequent industrialization. Since then, mechanisms for hoarding and privatizing land and water have been consolidated and deepened in the 20th century with neoliberal policies, resulting in a socio-environmental crisis that affects communities, particularly indigenous peoples and precarious sectors.

A land donation to a data center that was revoked in Brazil

In October 2022, in the state of Pernambuco, Brazil, a state law authorized the donation of ≈8,000–8,200 m² of the 120,000 m² Arcoverde Memorial Park (an area used by the public museum Espaço Ciência, located on the border between Recife and Olinda) for the installation of a data center and a landing station for submarine internet cables.

However, following public opposition, the Pernambuco government definitively revoked the donation in 2025 (Melo, 2025). There were many public arguments against the state donation, including (MPPE, 2023):

- The lack of transparency regarding environmental studies that took into account the mangrove area preserved there.

- The protection of the heritage of the Olinda Historic Site, a protected area within the boundaries of the Olinda Historic Site.

- The vindication of Espacio Ciencia as an essential point in a scientific-tourist itinerary through Recife and Olinda, as its loss of character would destroy part of the economic potential of both cities.